Back القوانين الغذائية في المسيحية Arabic القوانين الغذائيه فى المسيحيه ARZ Christian dietary laws English Dieta en el cristianismo Spanish നോമ്പ് (ക്രിസ്തീയം) Malayalam Християнська дієта Ukrainian

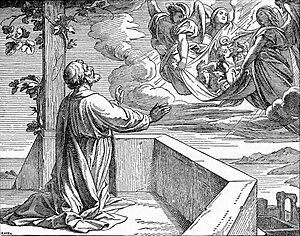

Dalam Kekristenan Nikea arus utama, tiada batasan terhadap jenis hewan yang dapat disantap.[1][2] Praktek tersebut bermula dari penglihatan Petrus dari sebuah lembar dengan hewan-hewan, yang dikisahkan dalam Kisah Para Rasul, Pasal 10, dimana Santo Petrus "melihat sebuah lembar berisi hewan-hewan yang diturunkan dari langit."[3] Selain itu, Perjanjian Baru hanya memberikan sedikit panduan terhadap konsumsi daging, yang diterapkan oleh Gereja Kristen saat ini; seseorang dilarang menyantap makanan yang diketahui dipersembahkan kepada berhala-berhala pagan,[4] sebuah perintah yang dikotbahkan oleh Bapa-bapa Gereja perdana, seperti Klemens dari Aleksandria dan Origenes.[5] Selain itu, umat Kristen biasanya memberkati makanan apapun sebelum disantap dengan doa makan, sebagai tanda terima kasih kepada Allah atas hidangan yang mereka miliki.

Menjagal hewan untuk dijadikan makanan biasanya dilakukan tanpa rumus Trinitarian,[6][7] meskipun Gereja Apostolik Armenia, di bandingkan Kristen Ortodoks lainnya, memiliki ritual mengikuti shechitah, aturan penjagalan Yahudi.[8] Menurut Norman Geisler, Alkitab memerintahkan seseorang untuk "menjauhi makanan yang dipersembahkan kepada berhala, mengandung darah, mengandung daging dari hewan-hewan yang dicekik".[9]

Terdapat pula sejumlah kelompok yang memiliki pantang makanan tertentu, seperti beberapa biarawan Kristen, seperti Trapis, mengadopsi kewajiban vegetarianisme Kristen.[10] Selain itu, umat Kristen dari tradisi Adventis Hari Ketujuh umumnya "berpantang menyantap daging dan makanan berbumbu pekat".[11] Umat Kristen dalam aliran-aliran Anglikan, Katolik, Lutheran, Methodis dan Ortodoks biasanya menjalankan hari pantang daging, khususnya pada musim liturgi Prapaskah.[12][13][14][15]

- ^ Wright, Professor Robin M; Vilaça, Aparecida (28 May 2013). Native Christians: Modes and Effects of Christianity among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. hlm. 171. ISBN 978-1-4094-7813-3.

Before Christianity, they could not eat certain things from certain animals (uumajuit), but after eating they can now do anything they want to.

- ^ Geisler, Norman L. (1 September 1989). Christian Ethics: Contemporary Issues and Options (dalam bahasa English). Baker Books. hlm. 334. ISBN 978-1-58558-053-8.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (1 May 2006). Peter, Paul, and Mary Magdalene: The Followers of Jesus in History and Legend (dalam bahasa English). Oxford University Press. hlm. 60. ISBN 978-0-19-974113-7. Diakses tanggal 2 May 2014.

In the meantime, Peter in Joppa has a midday vision in which he sees a sheet containing animals of every description lowered from the sky. He hears a voice from heaven telling him to "kill and eat." Peter is naturally taken aback, because eating some of these animals would mean breaking the Jewish rules about kosher foods. But then he hears a voice that tells him, "What God has cleansed, you must not call common [unclean]" (that is, you do not need to refrain from eating nonkosher foods; 10: 15). The same sequence of events happens three times.

- ^ "The Weaker Brother". Third Way Magazine. 25 (10): 25. December 2002.

Christ came for the Gentiles as well as the Jews (the real meaning of that vision in Acts 10:9;16) but he also calls us to look out for each other and not do things that will cause our brothers and sisters to stumble. In Corinthians Paul urges the believers to consider not eating meat when with people who assume that meat must be offered to idols before consumption: 'Food will not bring us close to God,' he writes. 'We are no worse off if we do not eat, and no better off if we do. But take care that this liberty of yours does not somehow become a stumbling block for the weak.' (1 Corinthians 8:8-9)

- ^ Binder, Stephanie E. (2012-11-14). Tertullian, On Idolatry and Mishnah Avodah Zarah (dalam bahasa English). Brill Academic Publishers. hlm. 87. ISBN 978-90-04-23478-9.

Clement of Alexandria and Origen also forbid eating meat dedicated to idolatry and partaking in meals with demons, which, by association, are the meals of fornicators and idolatrous adulterers. Marcianus Aristides merely testifies that Christians do not eat what has been sacrificed to idols; and Hippolytus only notes the interdiction against eating such food.

- ^ Salamon, Hagar (7 November 1999). Ethiopian Jews in Christian Ethiopia (dalam bahasa English). University of California Press. hlm. 101. ISBN 978-0-520-92301-0.

The Christians do "Basema ab wawald wamanfas qeeus ahadu amlak" [in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit one God] and then slaughter. The Jews say "Baruch yitharek amlak yisrael" [Blessed is the King (God) of Israel].

- ^ Efron, John M. (1 October 2008). Medicine and the German Jews: A History (dalam bahasa English). Yale University Press. hlm. 206. ISBN 978-0-300-13359-2.

By contrast, the most common mode of slaughtering four-legged animals among Christians in the nineteenth century was through the deliverance of a stunning blow to the head, usually with a mallet or poleax.

- ^ Grumett, David; Muers, Rachel (26 February 2010). Theology on the Menu: Asceticism, Meat and Christian Diet (dalam bahasa English). Routledge. hlm. 121. ISBN 978-1-135-18832-0.

The Armenian and other Orthodox rituals of slaughter display obvious links with shechitah, Jewish kosher slaughter.

- ^ Norman L. Geisler (1989). Christian Ethics. Baker Book. hlm. 206. ISBN 978-0-8010-3832-7.

- ^ Walters, Peter; Byl, John (2013). Christian Paths to Health and Wellness (dalam bahasa English). Human Kinetics. hlm. 184. ISBN 978-1-4504-2454-7.

Traditional Hindus and Trappist monks adopt vegetarian diets as a practice of their faith.

- ^ Daugherty, Helen Ginn (1995). An Introduction to Population

(dalam bahasa English). Guilford Press. hlm. 150. ISBN 978-0-89862-616-2.

(dalam bahasa English). Guilford Press. hlm. 150. ISBN 978-0-89862-616-2. Seventh-Day Adventists are also urged, but not required, to avoid eating meat and highly spiced food (Snowdon, 1988).

- ^ "What does The United Methodist Church say about fasting?" (dalam bahasa English). The United Methodist Church. Diakses tanggal 2 May 2014.[pranala nonaktif permanen]

- ^ Barrows, Susanna; Room, Robin (1991). Drinking: Behavior and Belief in Modern History (dalam bahasa English). University of California Press. hlm. 340. ISBN 978-0-520-07085-1. Diakses tanggal 2 May 2014.

The main legally enforced prohibition in both Catholic and Anglican countries was that against meat. During Lent, the most prominent annual season of fasting in Catholic and Anglican churches, authorities enjoined abstinence from meat and sometimes "white meats" (cheese, milk, and eggs); in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England butchers and victuallers were bound by heavy recognizances not to slaughter or sell meat on the weekly "fish days," Friday and Saturday.

- ^ Lund, Eric (January 2002). Documents from the History of Lutheranism, 1517-1750. Fortress Press. hlm. 166. ISBN 978-1-4514-0774-7.

Of the Eating of Meat: One should abstain from the eating of meat on Fridays and Saturdays, also in fasts, and this should be observed as an external ordinance at the command of his Imperial Majesty.

- ^ Vitz, Evelyn Birge (1991). A Continual Feast (dalam bahasa English). Ignatius Press. hlm. 80. ISBN 978-0-89870-384-9. Diakses tanggal 2 May 2014.

In the Orthodox groups, on ordinary Wednesdays and Fridays no meat, olive oil, wine, or fish can be consumed.