Back علم مسيحي Arabic علم مسيحى ARZ Ciència Cristiana Catalan Křesťanská věda Czech Seientiaeth Gristnogol Welsh Christian Science Danish Christian Science German Kristana Scienco Esperanto Ciencia cristiana Spanish علم مسیحی Persian

| Christian Science | |

|---|---|

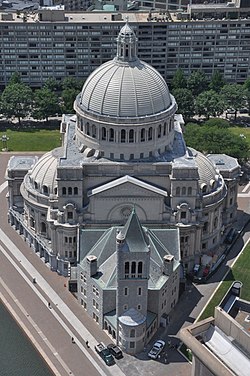

The First Church of Christ, Scientist at the Christian Science Center in Boston with the original Mother Church (1894) in the foreground and the Mother Church Extension (1906) behind it.[1] | |

| Scripture | Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy and the Bible |

| Theology | "Basic teachings", Church of Christ, Scientist |

| Founder | Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1910) |

| Members | Estimated 106,000 in the United States in 1990[2] and under 50,000 in 2009;[3] according to the church, 400,000 worldwide in 2008.[n 1] |

| Official website | christianscience.com |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Christian Science |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

Christian Science is a set of beliefs and practices which are associated with members of the Church of Christ, Scientist. Adherents are commonly known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science, and the church is sometimes informally known as the Christian Science church. It was founded in 1879 in New England by Mary Baker Eddy, who wrote the 1875 book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, which outlined the theology of Christian Science. The book was originally called Science and Health; the subtitle with a Key to the Scriptures was added in 1883 and later amended to with Key to the Scriptures.[5]

The book became Christian Science's central text, along with the Bible, and by 2001 had sold over nine million copies.[6]

Eddy and 26 followers were granted a charter by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1879 to found the "Church of Christ (Scientist)"; the church would be reorganized under the name "Church of Christ, Scientist" in 1892.[7] The Mother Church, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, was built in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1894.[8] Known as the "thinker's religion," Christian Science became the fastest growing religion in the United States, with nearly 270,000 members by 1936 — a figure which had declined to just over 100,000 by 1990[9] and reportedly to under 50,000 by 2009.[3] The church is known for its newspaper, The Christian Science Monitor, which won seven Pulitzer Prizes between 1950 and 2002, and for its public Reading Rooms around the world.[n 2]

Christian Science's religious tenets differ considerably from many other Christian denominations, including key concepts such as the Trinity, the divinity of Jesus, atonement, the resurrection, and the Eucharist.[11][12] Eddy, for her part, described Christian Science as a return to "primitive Christianity and its lost element of healing".[13] Adherents subscribe to a radical form of philosophical idealism, believing that reality is purely spiritual and the material world an illusion.[14] This includes the view that disease is a mental error rather than physical disorder, and that the sick should be treated not by medicine but by a form of prayer that seeks to correct the beliefs responsible for the illusion of ill health.[15][16]

The church does not require that Christian Scientists avoid medical care—adherents use dentists, optometrists, obstetricians, physicians for broken bones, and vaccination when required by law—but maintains that Christian Science prayer is most effective when not combined with medicine.[17][18] The reliance on prayer and avoidance of medical treatment has been blamed for the deaths of several adherents and their children. Between the 1880s and 1990s, parents and others were prosecuted for, and in a few cases convicted of, manslaughter or neglect.[19]

- ^ "Christian Science Center Complex" Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine, Boston Landmarks Commission, Environment Department, City of Boston, January 25, 2011 (hereafter Boston Landmarks Commission 2011), pp. 6–12.

- ^ Stark, Rodney (1998). "The Rise and Fall of Christian Science". Journal of Contemporary Religion. 13 (2): (189–214), 191. doi:10.1080/13537909808580830.

- ^ a b Prothero, Donald; Callahan, Timothy D. (2017). UFOs, Chemtrails, and Aliens: What Science Says. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 165.

- ^ Valente, Judy (August 1, 2008). "Christian Science Healing". PBS.

- ^ "140th Anniversary of Science and Health". Mary Baker Eddy Library. July 7, 2015.

- ^ Gutjahr, Paul C. (2001). "Sacred Texts in the United States". Book History. 4: (335–370) 348. doi:10.1353/bh.2001.0008. JSTOR 30227336. S2CID 162339753.

- ^ "Women and the Law". The Mary Baker Eddy Library. 22 January 2016. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021.

- ^ For the charter, Eddy, Mary Baker (1908) [1895]. Manual of the Mother Church, 89th edition. Boston: The First Church of Christ, Scientist. pp. 17–18.

- ^ Stark 1998, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Fuller 2011, p. 175

- ^ Fraser 1999, pp. 131-132.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 124.

- ^ Wilson, Bryan (1961). Sects and Society: A Sociological Study of the Elim Tabernacle, Christian Science, and Christadelphians. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 125.

Eddy, Manual of the Mother Church, p. 17.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 127; Rescher, Nicholas (2009) [1996]. "Idealism", in Jaegwon Kim, Ernest Sosa (eds.). A Companion to Metaphysics. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 318 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Wilson 1961, p. 125.

- ^ Battin, Margaret P. (1999). "High-Risk Religion: Christian Science and the Violation of Informed Consent". In DesAutels, Peggy; Battin, Margaret P.; May, Larry (eds.). Praying for a Cure: When Medical and Religious Practices Conflict. Lanham, MD, and Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 0-8476-9262-0.

- ^ Schoepflin, Rennie B. (2003). Christian Science on Trial: Religious Healing in America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 192–193.

Trammell, Mary M., chair, Christian Science board of directors (March 26, 2010). "Letter; What the Christian Science Church Teaches" Archived 2022-08-07 at the Wayback Machine. The New York Times.

- ^ Regarding vaccines specifically, see:

- Christine Pae (September 1, 2021). "Here's who qualifies for a religious exemption to Washington's COVID-19 vaccine mandate". Archived 2021-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. KING 5.

- Samantha Maiden (April 18, 2015). "No Jab, No Pay reforms: Religious exemptions for vaccination dumped". Archived 2021-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Daily Telegraph (Australia).

- ^ Schoepflin 2003, pp. 212–216 Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine; Peters, Shawn Francis (2007). When Prayer Fails: Faith Healing, Children, and the Law. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 91, 109–130. Archived 2022-11-01 at the Wayback Machine.

Cite error: There are <ref group=n> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=n}} template (see the help page).