Back Klimaatsverandering Afrikaans Klimawandel ALS تغير المناخ Arabic تبدال د لمناخ ARY تغير المناخ ARZ Cambéu climáticu AST İqlim dəyişikliyi Azerbaijani ایقلیم دییشیکلیگی AZB Pagbago kan klima BCL Змена клімату Byelorussian

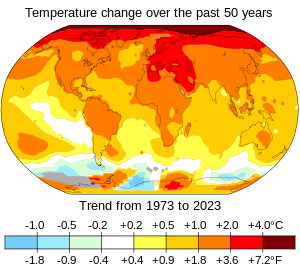

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth’s climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to Earth's climate. The current rise in global temperatures is driven by human activities, especially fossil fuel burning since the Industrial Revolution.[3][4] Fossil fuel use, deforestation, and some agricultural and industrial practices release greenhouse gases.[5] These gases absorb some of the heat that the Earth radiates after it warms from sunlight, warming the lower atmosphere. Carbon dioxide, the primary gas driving global warming, has increased in concentration by about 50% since the pre-industrial era to levels not seen for millions of years.[6]

Climate change has an increasingly large impact on the environment. Deserts are expanding, while heat waves and wildfires are becoming more common.[7] Amplified warming in the Arctic has contributed to thawing permafrost, retreat of glaciers and sea ice decline.[8] Higher temperatures are also causing more intense storms, droughts, and other weather extremes.[9] Rapid environmental change in mountains, coral reefs, and the Arctic is forcing many species to relocate or become extinct.[10] Even if efforts to minimize future warming are successful, some effects will continue for centuries. These include ocean heating, ocean acidification and sea level rise.[11]

Climate change threatens people with increased flooding, extreme heat, increased food and water scarcity, more disease, and economic loss. Human migration and conflict can also be a result.[12] The World Health Organization calls climate change one of the biggest threats to global health in the 21st century.[13] Societies and ecosystems will experience more severe risks without action to limit warming.[14] Adapting to climate change through efforts like flood control measures or drought-resistant crops partially reduces climate change risks, although some limits to adaptation have already been reached.[15] Poorer communities are responsible for a small share of global emissions, yet have the least ability to adapt and are most vulnerable to climate change.[16][17]

Many climate change impacts have been observed in the first decades of the 21st century, with 2024 the warmest on record at +1.60 °C (2.88 °F) since regular tracking began in 1850.[19][20] Additional warming will increase these impacts and can trigger tipping points, such as melting all of the Greenland ice sheet.[21] Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, nations collectively agreed to keep warming "well under 2 °C". However, with pledges made under the Agreement, global warming would still reach about 2.8 °C (5.0 °F) by the end of the century.[22] Limiting warming to 1.5 °C would require halving emissions by 2030 and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.[23][24]

Fossil fuel use can be phased out by conserving energy and switching to energy sources that do not produce significant carbon pollution. These energy sources include wind, solar, hydro, and nuclear power.[25] Cleanly generated electricity can replace fossil fuels for powering transportation, heating buildings, and running industrial processes.[26] Carbon can also be removed from the atmosphere, for instance by increasing forest cover and farming with methods that capture carbon in soil.[27]

- ^ "GISS Surface Temperature Analysis (v4)". NASA. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 Summary for Policymakers 2021, SPM-7

- ^ Forster et al. 2024, p. 2626: "The indicators show that, for the 2014–2023 decade average, observed warming was 1.19 [1.06 to 1.30] °C, of which 1.19 [1.0 to 1.4] °C was human-induced."

- ^ Lynas, Mark; Houlton, Benjamin Z.; Perry, Simon (19 October 2021). "Greater than 99% consensus on human caused climate change in the peer-reviewed scientific literature". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (11): 114005. Bibcode:2021ERL....16k4005L. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac2966. ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 239032360.

- ^ Our World in Data, 18 September 2020

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 Technical Summary 2021, p. 67: "Concentrations of CO2, methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) have increased to levels unprecedented in at least 800,000 years, and there is high confidence that current CO2 concentrations have not been experienced for at least 2 million years."

- ^

- IPCC SRCCL 2019, p. 7: "Since the pre-industrial period, the land surface air temperature has risen nearly twice as much as the global average temperature (high confidence). Climate change... contributed to desertification and land degradation in many regions (high confidence)."

- IPCC AR6 WG2 SPM 2022, p. 9: "Observed increases in areas burned by wildfires have been attributed to human-induced climate change in some regions (medium to high confidence)"

- ^ IPCC SROCC 2019, p. 16: "Over the last decades, global warming has led to widespread shrinking of the cryosphere, with mass loss from ice sheets and glaciers (very high confidence), reductions in snow cover (high confidence) and Arctic sea ice extent and thickness (very high confidence), and increased permafrost temperature (very high confidence)."

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 Ch11 2021, p. 1517

- ^ EPA (19 January 2017). "Climate Impacts on Ecosystems". Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Mountain and arctic ecosystems and species are particularly sensitive to climate change... As ocean temperatures warm and the acidity of the ocean increases, bleaching and coral die-offs are likely to become more frequent.

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch1 2018, p. 64: "Sustained net zero anthropogenic emissions of CO2 and declining net anthropogenic non-CO2 radiative forcing over a multi-decade period would halt anthropogenic global warming over that period, although it would not halt sea level rise or many other aspects of climate system adjustment."

- ^

- ^ WHO, Nov 2023

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG2 SPM 2022, p. 19

- ^

- IPCC AR6 WG2 SPM 2022, pp. 21–26

- IPCC AR6 WG2 Ch16 2022, p. 2504

- IPCC AR6 SYR SPM 2023, pp. 8–9: "Effectiveness15 of adaptation in reducing climate risks16 is documented for specific contexts, sectors and regions (high confidence) ... Soft limits to adaptation are currently being experienced by small-scale farmers and households along some low-lying coastal areas (medium confidence) resulting from financial, governance, institutional and policy constraints (high confidence). Some tropical, coastal, polar and mountain ecosystems have reached hard adaptation limits (high confidence). Adaptation does not prevent all losses and damages, even with effective adaptation and before reaching soft and hard limits (high confidence)."

- ^ Tietjen, Bethany (2 November 2022). "Loss and damage: Who is responsible when climate change harms the world's poorest countries?". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability". IPCC. 27 February 2022. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ Ivanova, Irina (2 June 2022). "California is rationing water amid its worst drought in 1,200 years". CBS News.

- ^ "2024 - a second record-breaking year, following the exceptional 2023". Copernicus Programme. 10 January 2025. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (10 January 2025). "Hottest year on record sent planet past 1.5C of heating for first time in 2024". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 January 2025.

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG1 Technical Summary 2021, p. 71

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme 2024, p. XVIII: "The full implementation and continuation of the level of mitigation effort implied by unconditional or conditional NDC scenarios lower these projections to 2.8 °C (range: 1.9–3.7) and 2.6 °C (range: 1.9–3.6), respectively. All with at least a 66 per cent chance."

- ^ IPCC SR15 Ch2 2018, pp. 95–96: "In model pathways with no or limited overshoot of 1.5 °C, global net anthropogenic CO2 emissions decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 (40–60% interquartile range), reaching net zero around 2050 (2045–2055 interquartile range)"

- ^ IPCC SR15 2018, p. 17, SPM C.3: "All pathways that limit global warming to 1.5 °C with limited or no overshoot project the use of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) on the order of 100–1000 GtCO2 over the 21st century. CDR would be used to compensate for residual emissions and, in most cases, achieve net negative emissions to return global warming to 1.5 °C following a peak (high confidence). CDR deployment of several hundreds of GtCO2 is subject to multiple feasibility and sustainability constraints (high confidence)."

- ^

- IPCC AR5 WG3 Annex III 2014, p. 1335

- IPCC AR6 WG3 Summary for Policymakers 2022, pp. 24–25

- IPCC AR6 WG3 Technical Summary 2022, p. 89

- ^ IPCC AR6 WG3 Technical Summary 2022, p. 84: "Stringent emissions reductions at the level required for 2°C or 1.5°C are achieved through the increased electrification of buildings, transport, and industry, consequently all pathways entail increased electricity generation (high confidence)."

- ^

![A dry lakebed in California, which is experiencing its worst megadrought in 1,200 years.[18]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d3/California_Drought_Dry_Lakebed_2009.jpg/129px-California_Drought_Dry_Lakebed_2009.jpg)