Back Volstruis Afrikaans ሰጎን Amharic Struthio camelus AN Strȳta ANG نعام شائع Arabic نعامه شائعه ARZ Struthio camelus AST ВаранихӀинчӀ AV دوهقوشو AZB Африка дөйәғошо Bashkir

| Common ostrich | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| South African (S. c. australis) male (left) and females | |||||

| Scientific classification | |||||

| Domain: | Eukaryota | ||||

| Kingdom: | Animalia | ||||

| Phylum: | Chordata | ||||

| Class: | Aves | ||||

| Infraclass: | Palaeognathae | ||||

| Order: | Struthioniformes | ||||

| Family: | Struthionidae | ||||

| Genus: | Struthio | ||||

| Species: | S. camelus

| ||||

| Binomial name | |||||

| Struthio camelus | |||||

| Subspecies[3] | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

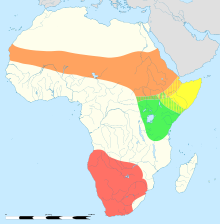

Struthio distribution map

| |||||

| Synonyms[4][5][6][7][8] | |||||

|

List

| |||||

The common ostrich (Struthio camelus), or simply ostrich, is a species of flightless bird native to certain areas of Africa. It is one of two extant species of ostriches, the only living members of the genus Struthio in the ratite order of birds. The other is the Somali ostrich (Struthio molybdophanes), which has been recognized as a distinct species by BirdLife International since 2014, having been previously considered a distinctive subspecies of ostrich.[3][9]

The common ostrich belongs to the order Struthioniformes. Struthioniformes previously contained all the ratites, such as the kiwis, emus, rheas, and cassowaries. However, recent genetic analysis has found that the group is not monophyletic, as it is paraphyletic with respect to the tinamous, so the ostriches are now classified as the only members of the order.[10][11] Phylogenetic studies have shown that it is the sister group to all other members of Palaeognathae, and thus the flighted tinamous are the sister group to the extinct moa.[12][13] It is distinctive in its appearance, with a long neck and legs, and can run for a long time at a speed of 55 km/h (34 mph)[14] with short bursts up to about 97 km/h (60 mph),[15] the fastest land speed of any bipedal animal and the second fastest of all land animals after the Cheetah.[16][17] The common ostrich is the largest living species of bird and thus the largest living dinosaur.[18] It lays the largest eggs of any living bird (the extinct giant elephant bird (Aepyornis maximus) of Madagascar and the south island giant moa (Dinornis robustus) of New Zealand laid larger eggs). Ostriches are the most dangerous birds on the planet for humans, with an average of two to three deaths being recorded each year in South Africa.[19]

The common ostrich's diet consists mainly of plant matter, though it also eats invertebrates and small reptiles. It lives in nomadic groups of 5 to 50 birds. When threatened, the ostrich will either hide itself by lying flat against the ground or run away. If cornered, it can attack with a kick of its powerful legs. Mating patterns differ by geographical region, but territorial males fight for a harem of two to seven females.

The common ostrich is farmed around the world, particularly for its feathers, which are decorative and are also used as feather dusters. Its skin is used for leather products and its meat is marketed commercially, with its leanness a common marketing point.[15]

- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Struthio camelus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T45020636A132189458. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T45020636A132189458.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

SNwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gray, George Robert (1849). The Genera of Birds Comprising Their Generic Characters, a Notice of the Habits of Each Genus, and an Extensive List of Species Referred to Their Several Genera (3 ed.). London, Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, Paternoster-Row: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, Paternoster-Row. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ Gurney, J. H. (July 1868). "Notes on Mr. Layard's 'Birds of South Africa'". The Ibis. 4 (15): 253–254. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.1868.tb06118.x. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ Neumann, Oscar (1898). "Beiträge zur Vogelfauna von Ost- und Central-Afrika". Journal für Ornithologie. 46: 243. doi:10.1007/bf02208449. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ Stresemann, Erwin (1926). "Die Vogelausbeute des Herrn Paul Spatz in Rio de Oro". Ornithologische Monatsberichte. 34 (5): 138.

- ^ Grant, C. H. B.; Mackworth-Praed, C. W. (1951). "On the Type Locality of Struthio camelus Linnaeus, and Description of a New Race". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 71 (7): 45–46. Retrieved 1 December 2024.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Struthio molybdophanes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22732795A95049558. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- ^ Yuri, Tamaki; Kimball, Rebecca; Harshman, John; Bowie, Rauri; Braun, Michael; Chojnowski, Jena; Han, Kin-Lan; Hackett, Shannon; Huddleston, Christopher; Moore, William; Reddy, Sushma (13 March 2013). "Parsimony and Model-Based Analyses of Indels in Avian Nuclear Genes Reveal Congruent and Incongruent Phylogenetic Signals". Biology. 2 (1): 419–444. doi:10.3390/biology2010419. ISSN 2079-7737. PMC 4009869. PMID 24832669.

- ^ Clarke, Andrew (14 July 2008). Faculty of 1000 evaluation for A phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history (Report). doi:10.3410/f.1115666.571731.

- ^ Mitchell, K. J.; Llamas, B.; Soubrier, J.; Rawlence, N. J.; Worthy, T. H.; Wood, J.; Lee, M. S. Y.; Cooper, A. (23 May 2014). "Ancient DNA reveals elephant birds and kiwi are sister taxa and clarifies ratite bird evolution" (PDF). Science. 344 (6186): 898–900. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..898M. doi:10.1126/science.1251981. hdl:2328/35953. PMID 24855267. S2CID 206555952.

- ^ Baker, A. J.; Haddrath, O.; McPherson, J. D.; Cloutier, A. (2014). "Genomic Support for a Moa-Tinamou Clade and Adaptive Morphological Convergence in Flightless Ratites". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (7): 1686–1696. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu153. PMID 24825849.

- ^ Sellers, W. I.; Manning, P. L. (2007). "Estimating dinosaur maximum running speeds using evolutionary robotics". Proc. R. Soc. B. 274 (1626): 2711–2716. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0846. PMC 2279215. PMID 17711833.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

Davieswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Dohertywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Explained: How Fast Can An Ostrich Run | BirdJoy". Bird Joy. 15 December 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ Physics World, February 2, 2017

- ^ Usurelu, Sergiu; Bettencourt, Vanessa; Melo, Gina (2015). "Abdominal trauma by ostrich". Annals of Medicine & Surgery. 4 (1): 41–43. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2014.12.004. PMC 4323753. PMID 25685344.

Cite error: There are <ref group=note> tags on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=note}} template (see the help page).