Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott | |

|---|---|

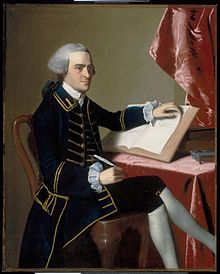

Oil painting of Dorothy Quincy, c. 1772 by Copley | |

| Born | May 10, 1747 |

| Died | February 3, 1830 (aged 82) Boston, Massachusetts, United States |

| Occupation(s) | 1st and 3rd First Lady of Massachusetts |

| Successor | Elizabeth Adams |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | Lydia Henchman Hancock (1776–1777), John George Washington Hancock (1778–1787) |

| Parent(s) | Edmund Quincy (1703–1788), Elizabeth Wendell (1704–1769)[1] |

Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott (/ˈkwɪnzi/; May 21 (May 10 O.S.) 1747 – February 3, 1830) was an American hostess, daughter of Justice Edmund Quincy of Braintree and Boston, and the wife of Founding Father John Hancock.[2] Her aunt, also named Dorothy Quincy, was the subject of Oliver Wendell Holmes' poem Dorothy Q.[3]

Dorothy Quincy was raised at the Quincy Homestead in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts. The house in which she lived has been designated a National Historic Landmark and is known as the Dorothy Quincy House. She married John Hancock, who presided at the formation of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and was a two-time Governor of Massachusetts, in 1775. Their first child, Lydia Henchman Hancock was born in 1776 and died ten months later.[4] In 1778, their son, John George Washington Hancock, was born and died in 1787 while ice skating on a pond in Milton, Massachusetts when he fell through the ice and drowned.[5]

In 1796, after Hancock's death in 1793, Quincy married Captain James Scott (1742–1809), who had been employed by Hancock as a captain in his trading ventures with England. They lived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and had no children together. When Captain Scott died, Dorothy moved back into the Hancock Mansion at 30 Beacon Street in Boston for about 10 years. After that, she lived at 4 Federal Street in Boston.[6]

Dorothy was a well-known hostess, and a great deal was written about her. Many chroniclers of the time note that she was beautiful, well-spoken, and intelligent. She witnessed the Battle of Lexington while staying with her future husband's aunt, Lydia Hancock, at the home of Rev. Jonas Clark, now known as the Hancock-Clarke House.[7] When Hancock told her after the battle that she could not go back to her father in Boston, she retorted, "Recollect Mr. Hancock, that I am not under your control yet. I shall go to my father tomorrow."[8]

During the American Revolution, the Hancocks hosted the Marquis de Lafayette, and in October 1781, he came to their house with the news that the British had surrendered at Yorktown. In 1824, Lafayette toured the United States at the invitation of President James Monroe. During the welcoming procession in Boston, where he was escorted by her nephew, Mayor Josiah Quincy III, Lafayette saw Dorothy Quincy watching from a balcony. He stopped his carriage, placed his hand on his heart, and bowed to her with tears in his eyes. She returned the gesture, burst into tears, and said, "I have lived long enough."[9]

In her novel, An Old-Fashioned Girl, Louisa May Alcott, Dorothy Quincy's great-grandniece, has her character, Grandma Shaw, witness Lafayette's visit. [10]

- ^ "Dorothy Quincy (Mrs. John Hancock)". March 14, 2018.

- ^ Cutter, William (1908). Genealogical & Personal Memoirs's Vol II. Lincoln: Nebraska: Lewis Historical Publish Co. p. 594.

- ^ Crawford, Mary Caroline (1902). The Romance of Old New England Rooftrees. L. C. Page & Company. pp. 117. Retrieved March 17, 2008.

- ^ Fowler, William M. Jr. (1980). The Baron of Beacon Hill: A Biography of John Hancock. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-27619-5.

- ^ Fowler1980, pp. 229, 265.

- ^ "Dorothy Quincy Hancock". Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ Wives of the Signers: The Women Behind the Declaration of Independence (1997), Harry Clinton Green, Mary Wolcott Green, and David Barton, pp. 18–32

- ^ Brown, R: "Incidents in the Life of John Hancock: as related by Dorthy Quincy Hancock Scott", Magazine of American History, Vol XIX:1888:506, Barnes, NY

- ^ LaPlante, Eve (2012). Marmee & Louisa. New York: Free Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4516-2066-5.

- ^ LaPlante2012, p. 35.