Back التوسعات المبكرة لأشباه البشر خارج إفريقيا Arabic Premières migrations des Hominines hors d'Afrique French התפשטות מוקדמת של הומינינים אל מחוץ לאפריקה HE Ekspansi hominini awal keluar Afrika ID Out of Africa I Italian 구인류의 탈아프리카 확장 Korean Ut av Afrika I NB له افریقا څخه بهر د هومینین انسانانو لومړنۍ تیتېدنه Pashto/Pushto ఆఫ్రికా నుండి హోమినిన్ల తొలి వలసలు Tegulu Phát tán hominin cổ khỏi châu Phi Vietnamese

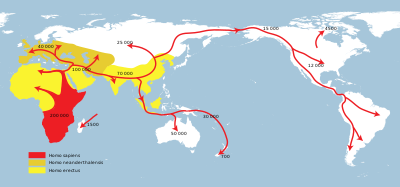

Several expansions of populations of archaic humans (genus Homo) out of Africa and throughout Eurasia took place in the course of the Lower Paleolithic, and into the beginning Middle Paleolithic, between about 2.1 million and 0.2 million years ago (Ma). These expansions are collectively known as Out of Africa I, in contrast to the expansion of Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) into Eurasia, which may have begun shortly after 0.2 million years ago (known in this context as "Out of Africa II").[1]

The earliest presence of Homo (or indeed any hominin) outside of Africa dates to close to 2 million years ago. A 2018 study claims hominin presence at Shangchen, central China, as early as 2.12 Ma based on magnetostratigraphic dating of the lowest layer containing stone artefacts.[2] The oldest known human skeletal remains outside of Africa are from Dmanisi, Georgia (Dmanisi skull 4), and are dated to 1.8 Ma. These remains are classified as Homo erectus georgicus.

Later waves of expansion are proposed around 1.4 Ma (early Acheulean industries), associated with Homo antecessor and 0.8 Ma (cleaver-producing Acheulean groups), associated with Homo heidelbergensis.[3]

Until the early 1980s, early humans were thought to have been restricted to the African continent in the Early Pleistocene, or until about 0.8 Ma; Hominin migrations outside East Africa were apparently rare in the Early Pleistocene, leaving a fragmentary record of events.[4][5]

- ^ The term "Out of Africa I" is informal and somewhat rare. The phrase Out of Africa used on its own generally refers to "Out of Africa II", the expansion of anatomically modern humans into Eurasia. "Out of Africa I" is used in 2004, in Marco Langbroek, 'Out of Africa': an investigation into the earliest occupation of the Old World, p. 61, and as the title of a collection of essays, J. G. Fleagle et al. (eds.), Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia (2010). see also: Herschkovitz, Israel; et al. (26 January 2018). "The earliest modern humans outside Africa". Science. 359 (6374): 456–459. Bibcode:2018Sci...359..456H. doi:10.1126/science.aap8369. hdl:10072/372670. PMID 29371468.; Hurtley, Stella; Szuromi, Phil (2005). "Out of Africa Revisited". Science. 308 (5724): 922. doi:10.1126/science.308.5724.921g. S2CID 220100436.

- ^ Zhu Zhaoyu (朱照宇); Dennell, Robin; Huang Weiwen (黄慰文); Wu Yi (吴翼); Qiu Shifan (邱世藩); Yang Shixia (杨石霞); Rao Zhiguo (饶志国); Hou Yamei (侯亚梅); Xie Jiubing (谢久兵); Han Jiangwei (韩江伟); Ouyang Tingping (欧阳婷萍) (2018). "Hominin occupation of the Chinese Loess Plateau since about 2.1 million years ago". Nature. 559 (7715): 608–612. Bibcode:2018Natur.559..608Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0299-4. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 29995848. S2CID 49670311. "Eight major magnetozones are recorded in the Shangchen section, four of which have normal polarity (N1 to N4) and four of which have reversed polarity (R1 to R4). By comparison with the geomagnetic polarity timescale [...] magnetozone N4 corresponds to the Réunion excursion (2.13–2.15 Ma) in L28."

- ^ Bar-Yosef, O.; Belfer-Cohen, A. (2001). "From Africa to Eurasia – early dispersals". Quaternary International. 75 (1): 19–28. Bibcode:2001QuInt..75...19B. doi:10.1016/S1040-6182(00)00074-4.

- ^ Lahr, M. M. (2010). "Saharan Corridors and Their Role in the Evolutionary Geography of 'Out of Africa I'". In Baden, A.; et al. (eds.). Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia. Springer Netherlands. pp. 27–46. ISBN 978-90-481-9035-5.

- ^ Straus, L. G.; Bar-Yosef, O. (2001). "Out of Africa in the Pleistocene: an introduction". Quaternary International. 75 (1): 2–4. Bibcode:2001QuInt..75....1S. doi:10.1016/s1040-6182(00)00071-9.