Back بطانة الرحم Arabic Эндаметрый Byelorussian Endometrij BS Endometri Catalan Děložní sliznice Czech Endometrium German Ενδομήτριο Greek Endometrio Esperanto Endometrio Spanish Emakalimaskest Estonian

| Endometrium | |

|---|---|

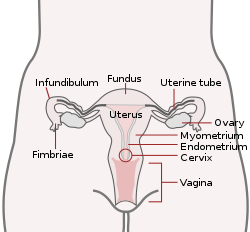

Uterus and fallopian tubes (uterine tubes). (Endometrium labeled at center right.) | |

Endometrium in the proliferative phase | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Uterus |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | tunica mucosa uteri |

| MeSH | D004717 |

| TA98 | A09.1.03.027 |

| TA2 | 3521 |

| FMA | 17742 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The endometrium is the inner epithelial layer, along with its mucous membrane, of the mammalian uterus. It has a basal layer and a functional layer: the basal layer contains stem cells which regenerate the functional layer.[1] The functional layer thickens and then is shed during menstruation in humans and some other mammals, including other apes, Old World monkeys, some species of bat, the elephant shrew[2] and the Cairo spiny mouse.[3] In most other mammals, the endometrium is reabsorbed in the estrous cycle. During pregnancy, the glands and blood vessels in the endometrium further increase in size and number. Vascular spaces fuse and become interconnected, forming the placenta, which supplies oxygen and nutrition to the embryo and fetus.[4][5] The speculated presence of an endometrial microbiota[6] has been argued against.[7][8]

- ^ Gargett, C.E.; Schwab, K.E.; Zillwood, R.M.; Nguyen, H.P.; Wu, D. (June 2009). "Isolation and culture of epithelial progenitors and mesenchymal stem cells from human endometrium". Biology of Reproduction. 80 (6): 1136–1145. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.108.075226. PMC 2849811. PMID 19228591.

- ^ Emera, D; Romero, R; Wagner, G (January 2012). "The evolution of menstruation: a new model for genetic assimilation: explaining molecular origins of maternal responses to fetal invasiveness". BioEssays. 34 (1): 26–35. doi:10.1002/bies.201100099. PMC 3528014. PMID 22057551.

- ^ Bellofiore, N.; Ellery, S.; Mamrot, J.; Walker, D.; Temple-Smith, P.; Dickinson, H. (2016-06-03). "First evidence of a menstruating rodent: the spiny mouse (Acomys cahirinus)". bioRxiv. 216 (1): 40.e1–40.e11. doi:10.1101/056895. PMID 27503621. S2CID 196624853.

- ^ Blue Histology - Female Reproductive System Archived 2007-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. School of Anatomy and Human Biology — The University of Western Australia Accessed 20061228 20:35

- ^ Guyton AC, Hall JE, eds. (2006). "Chapter 81 Female Physiology Before Pregnancy and Female Hormones". Textbook of Medical Physiology (11th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. pp. 1018ff. ISBN 9780721602400.

- ^ Franasiak, Jason M.; Scott, Richard T. (2015). "Reproductive tract microbiome in assisted reproductive technologies". Fertility and Sterility. 104 (6): 1364–1371. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.012. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 26597628.

- ^ Baker, JM; Chase, DM; Herbst-Kralovetz, MM (2018). "Uterine Microbiota: Residents, Tourists, or Invaders?". Frontiers in Immunology. 9: 208. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00208. PMC 5840171. PMID 29552006.

- ^ Perez-Muñoz, ME; Arrieta, MC; Ramer-Tait, AE; Walter, J (28 April 2017). "A critical assessment of the "sterile womb" and "in utero colonization" hypotheses: implications for research on the pioneer infant microbiome". Microbiome. 5 (1): 48. doi:10.1186/s40168-017-0268-4. PMC 5410102. PMID 28454555.