Back Withaai Afrikaans Carcharodon carcharias AN قرش أبيض كبير Arabic قرش ابيض كبير ARZ Carcharodon carcharias AST Böyük ağ köpəkbalığı Azerbaijani بؤیوک آغ کؤپک بالیغی AZB Голяма бяла акула Bulgarian बिसाल सफेद शार्क Bihari সাদা হাঙ্গর Bengali/Bangla

| Great white shark Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Male off Isla Guadalupe, Mexico | |

| |

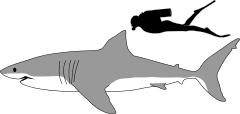

| Size comparison with human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | Lamnidae |

| Genus: | Carcharodon A. Smith, 1838 |

| Species: | C. carcharias

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharodon carcharias | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), also known as the white shark, white pointer, or simply great white, is a species of large mackerel shark which can be found in the coastal surface waters of all the major oceans. It is the only known surviving species of its genus Carcharodon. The great white shark is notable for its size, with the largest preserved female specimen measuring 5.83 m (19.1 ft) in length and around 2,000 kg (4,400 lb) in weight at maturity.[3] However, most are smaller; males measure 3.4 to 4.0 m (11 to 13 ft), and females measure 4.6 to 4.9 m (15 to 16 ft) on average.[4][5] According to a 2014 study, the lifespan of great white sharks is estimated to be as long as 70 years or more, well above previous estimates,[6] making it one of the longest lived cartilaginous fishes currently known.[7] According to the same study, male great white sharks take 26 years to reach sexual maturity, while the females take 33 years to be ready to produce offspring.[8] Great white sharks can swim at speeds of 25 km/h (16 mph)[9] for short bursts and to depths of 1,200 m (3,900 ft).[10]

The great white shark is arguably the world's largest-known extant macropredatory fish, and is one of the primary predators of marine mammals, such as pinnipeds and dolphins. The great white shark is also known to prey upon a variety of other animals, including fish, other sharks, and seabirds. It has only one recorded natural predator, the orca.[11]

The species faces numerous ecological challenges which has resulted in international protection. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the great white shark as a vulnerable species,[1] and it is included in Appendix II of CITES.[12] It is also protected by several national governments, such as Australia (as of 2018).[13] Due to their need to travel long distances for seasonal migration and extremely demanding diet, it is not logistically feasible to keep great white sharks in captivity; because of this, while attempts have been made to do so in the past, there are no known aquariums in the world believed to house a live specimen.[14]

The great white shark is depicted in popular culture as a ferocious man-eater, largely as a result of the novel Jaws by Peter Benchley and its subsequent film adaptation by Steven Spielberg. Humans are not a preferred prey,[15] but nevertheless it is responsible for the largest number of reported and identified fatal unprovoked shark attacks on humans.[16] However, attacks are rare, typically occurring fewer than 10 times per year globally.[17][18]

- ^ a b Rigby, C.L.; Barreto, R.; Carlson, J.; Fernando, D.; Fordham, S.; Francis, M.P.; Herman, K.; Jabado, R.W.; Jones, G.C.A.; Liu, K.M.; Lowe, C.G.; Marshall, A.; Pacoureau, N.; Romanov, E.; Sherley, R.B.; Winker, H. (2022) [amended version of 2019 assessment]. "Carcharodon carcharias". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T3855A212629880. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T3855A212629880.en. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ Soldo, A.; Bradai, M.N.; Walls, R. (2015). "Carcharodon carcharias (Europe assessment)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T3855A48948790. Retrieved 22 January 2025.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

DMGO03was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Viegas, Jennifer. "Largest Great White Shark Don't Outweigh Whales, but They Hold Their Own". Discovery Channel. Archived from the original on 7 February 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ^ Parrish, M. "How Big are Great White Sharks?". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History Ocean Portal. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ "Carcharodon carcharias". Animal Diversity Web. Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ "New study finds extreme longevity in white sharks". Science Daily. 9 January 2014. Archived from the original on 4 August 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- ^ Ghose, Tia (19 February 2015). "Great White Sharks Are Late Bloomers". LiveScience.com. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Klimley, A. Peter; Le Boeuf, Burney J.; Cantara, Kelly M.; Richert, John E.; Davis, Scott F.; Van Sommeran, Sean; Kelly, John T. (19 March 2001). "The hunting strategy of white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) near a seal colony". Marine Biology. 138 (3): 617–636. Bibcode:2001MarBi.138..617K. doi:10.1007/s002270000489. ISSN 0025-3162. S2CID 85018712.

- ^ Thomas, Pete (5 April 2010). "Great white shark amazes scientists with 4,000-foot dive into abyss". GrindTV. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012.

- ^ Currents of Contrast: Life in Southern Africa's Two Oceans. Struik. 2005. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-1-77007-086-8.

- ^ "Carcharodon carcharias". UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species On the World Wide Web. Archived from the original on 26 May 2024. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ Recovery Plan for the White Shark (Carcharodon carcharias) (Report). Government of Australia Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. 2013. Archived from the original on 24 January 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ Cronin, Melissa (10 January 2016). "Here's Why We've Never Been Able to Tame the Great White Shark". Archived from the original on 17 May 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ Hile, Jennifer (23 January 2004). "Great White Shark Attacks: Defanging the Myths". Marine Biology. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 2 May 2010.

- ^ "ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark". Florida Museum of Natural History University of Florida. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- ^ "Species Implicated in Attacks". Florida Museum. 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ rice, doyle. "2020 was an 'unusually deadly year' for shark attacks, with the most deaths since 2013". usa today. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021.