Back Koninkryk Hawaii Afrikaans Hawaii Cyning ANG مملكة هاواي Arabic Кралство Хаваи Bulgarian হাওয়াই রাজ্য Bengali/Bangla Regne de Hawaii Catalan Havajské království Czech Teyrnas Hawai'i Welsh Kongeriget Hawai‘i Danish Königreich Hawaiʻi German

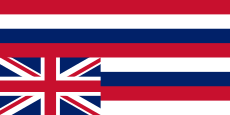

Hawaiian Kingdom Ke Aupuni Hawai‘i (Hawaiian) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1795–1893 | |||||||||||||||||

Motto:

| |||||||||||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Hawaiian, English | ||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Church of Hawaii | ||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Hawaiian | ||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy (1795—1840) Semi-constitutional monarchy (1840—1887) Constitutional monarchy (1887—1893) | ||||||||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||||||||

• 1795–1819 (first) | Kamehameha I | ||||||||||||||||

• 1891–1893 (last) | Liliʻuokalani | ||||||||||||||||

| Kuhina Nui | |||||||||||||||||

• 1819–1832 (first) | Kaʻahumanu | ||||||||||||||||

• 1863–1864 (last) | Kekūanaōʻa | ||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Legislature | ||||||||||||||||

| House of Nobles | |||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | |||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||

• Inception | May, 1795 | ||||||||||||||||

| March/April 1810[10] | |||||||||||||||||

| October 8, 1840 | |||||||||||||||||

| February 25 – July 31, 1843 | |||||||||||||||||

| November 28, 1843 | |||||||||||||||||

| August 22, 1849 – September 5, 1849 | |||||||||||||||||

| January 17, 1893 | |||||||||||||||||

• Forced abdication of Queen Liliʻuokalani | January 24, 1895 | ||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||

• 1780 | 400,000–800,000 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1800 | 250,000 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1832 | 130,313 | ||||||||||||||||

• 1890 | 89,990 | ||||||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Hawaiian sovereignty movement |

|---|

|

| Main issues |

| Governments |

| Historical conflicts |

| Modern events |

| Parties and organizations |

| Documents and ideas |

| Books |

The Hawaiian Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian: Ke Aupuni Hawaiʻi), was an archipelagic country from 1795 to 1893, which eventually encompassed all of the inhabited Hawaiian Islands. It was established in 1795 when Kamehameha I, then Aliʻi nui of Hawaii, conquered the islands of Oʻahu, Maui, Molokaʻi, and Lānaʻi, and unified them under one government. In 1810, the Hawaiian Islands were fully unified when the islands of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau voluntarily joined the Hawaiian Kingdom. Two major dynastic families ruled the kingdom, the House of Kamehameha and the House of Kalākaua.

The kingdom subsequently gained diplomatic recognition from European powers and the United States. An influx of European and American explorers, traders, and whalers soon began arriving to the kingdom, introducing diseases such as syphilis, tuberculosis, smallpox, and measles, leading to the rapid decline of the Native Hawaiian population. In 1887, King Kalākaua was forced to accept a new constitution after a coup d'état by the Honolulu Rifles, a volunteer military unit recruited from American settlers. Queen Liliʻuokalani, who succeeded Kalākaua in 1891, tried to abrogate the new constitution. She was subsequently overthrown in a 1893 coup engineered by the Committee of Safety, a group of Hawaiian subjects who were mostly of American descent, and supported by the U.S. military.[12] The Committee of Safety dissolved the kingdom and established the Republic of Hawaii, intending for the U.S. to annex the islands, which it did on July 7, 1898, via the Newlands Resolution. Hawaii became part of the U.S. as the Territory of Hawaii until it became a U.S. state in 1959.

In 1993, the United States Senate passed the Apology Resolution, which acknowledged that "the overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi occurred with the active participation of agents and citizens of the United States" and "the Native Hawaiian people never directly relinquished to the United States their claims to their inherent sovereignty as a people over their national lands, either through the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi or through a plebiscite or referendum." Opposition to the U.S. annexation of Hawaii played a major role in the creation of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, which calls for Hawaiian independence from American rule.

- ^ Kanahele, George S. (1995). "Kamehameha's First Capital". Waikiki, 100 B.C. to 1900 A.D.: An Untold Story. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 90–102. ISBN 978-0-8248-1790-9.

- ^ Patricia Schultz (2007). 1,000 Places to See in the USA and Canada Before You Die. Workman Pub. p. 932. ISBN 978-0-7611-4738-1.

- ^ Bryan Fryklund (January 4, 2011). Hawaii: The Big Island. Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-58843-637-5.

- ^ FAP-30 (Honoapiilani Highway) Realignment, Puamana to Honokowai, Lahaina District, Maui County: Environmental Impact Statement. 1991. p. 14.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (November 5, 2013). The Americas: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-134-25930-4.

- ^ Patrick Vinton Kirch; Thérèse I. Babineau (1996). Legacy of the landscape: an illustrated guide to Hawaiian archaeological sites. University of Hawaii Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8248-1816-6.

- ^ Benjamin F. Shearer (2004). The Uniting States: Alabama to Kentucky. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 296. ISBN 978-0-313-33105-3.

- ^ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky (May 23, 2013). Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 352. ISBN 978-1-61069-248-9.

- ^ Engineering Magazine. Engineering Magazine Company. 1892. p. 286.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph Simpson (1965) [1938]. The Hawaiian Kingdom 1778–1854, Foundation and Transformation. Vol. 1. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-87022-431-X. Archived from the original on September 25, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- ^ Spencer, Thomas P. (1895). Kaua Kuloko 1895. Honolulu: Papapai Mahu Press Publishing Company. OCLC 19662315.

- ^ Schulz, Joy (2017). Hawaiian by Birth: Missionary Children, Bicultural Identity, and U.S. Colonialism in the Pacific. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 1–238. ISBN 978-0803285897.