Back Illinois (země) Czech Χώρα των Ιλλινόις Greek Ilinojsa Lando Esperanto País de los Ilinueses Spanish سرزمین ایلینوی Persian Pays des Illinois French Pays des Illinois Italian イリノイ郡 Japanese Ilinojų kraštas Lithuanian Pays des Illinois NB

| Pays des Illinois | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District of New France | |||||||||||||||

| 1675–1769 1801–1803 | |||||||||||||||

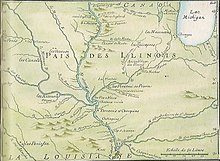

Illinois Country (Pais des Ilinois (sic)) 1717 | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Montreal (1675–1717) Biloxi (1717–1722) La Nouvelle-Orléans (after 1722) (regional: Chartres–after 1720; St Louis–after 1764) | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Foundation of the first mission at the Grand Village of the Illinois | 1675 | ||||||||||||||

• Transfer from French Canada to French Louisiana | 1717 | ||||||||||||||

| 1763 | |||||||||||||||

• Split east to Great Britain (Province of Quebec) | 1763 | ||||||||||||||

• East ceded to the United States | 1783 | ||||||||||||||

• Spanish retrocession of west to France | 1801 | ||||||||||||||

• West transferred to the United States | 1803 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | United States | ||||||||||||||

The Illinois Country (French: Pays des Illinois [pɛ.i dez‿i.ji.nwa]; lit. 'land of the Illinois people'; Spanish: País de los ilinueses), also referred to as Upper Louisiana (French: Haute-Louisiane [ot.lwi.zjan]; Spanish: Alta Luisiana), was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s that later fell under Spanish and British control before becoming what is now part of the Midwestern United States. While the area claimed included the entire Upper Mississippi River watershed, French colonial settlement was concentrated along the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers in what is now the U.S. states of Illinois and Missouri, with outposts on the Wabash River in Indiana. Explored in 1673 from Green Bay to the Arkansas River by the Canadien expedition of Louis Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, the area was claimed by France. It was settled primarily from the Pays d'en Haut in the context of the fur trade, and in the establishment of missions from Canada by French Catholic religious orders. Over time, the fur trade took some French to the far reaches of the Rocky Mountains, especially along the branches of the broad Missouri River valley. The "Illinois" in the territory's name is a reference to the Illinois Confederation, a group of related Algonquian native peoples.

The Illinois Country was governed from the French province of Canada until 1717 when, by order of King Louis XV, it was annexed to the French province of Louisiana, becoming known as "Upper Louisiana".[6] By the mid-18th century, major settlements included Cahokia, Kaskaskia, Chartres, Saint Philippe, and Prairie du Rocher, all on the east side of the Mississippi in present-day Illinois; and Ste. Genevieve across the river in what is now Missouri, as well as Fort Vincennes in what is now Indiana.[7]

As a consequence of the French defeat in the French and Indian War in 1764, the Illinois Country east of the Mississippi River was ceded to the British and became part of the British Province of Quebec; the land west of the river was ceded to Spanish Louisiana.

During the American Revolutionary War, Virginian George Rogers Clark led the Illinois campaign against the British. Illinois Country east of the Mississippi River along with what was then much of Ohio Country became part of Illinois County, Virginia, claimed by right of conquest. The county was abolished in 1782. In 1784, Virginia ceded its claims to the U.S. government and the area was incorporated as part of the Northwest Territory. The name lived on as Illinois Territory between 1809 and 1818, and as the State of Illinois after its admission to the union in 1818. The Spanish-occupied portion of Illinois Country west of the Mississippi was acquired by the United States from France in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

- ^ The Governor General of Canada (November 12, 2020). "Royal Banner of France - Heritage Emblem". Confirmation of the blazon of a Flag. February 15, 2008 Vol. V, p. 202. The Office of the Secretary to the Governor General.

- ^ New York State Historical Association (1915). Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association with the Quarterly Journal: 2nd−21st Annual Meeting with a List of New Members. The Association.

It is most probable that the Bourbon Flag was used during the greater part of the occupancy of the French in the region extending southwest from the St. Lawrence to the Mississippi, known as New France... The French flag was probably blue at that time with three golden fleur − de − lis ....

- ^ "Background: The First National Flags". The Canadian Encyclopedia. November 28, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

At the time of New France (1534 to the 1760s), two flags could be viewed as having national status. The first was the banner of France — a blue square flag bearing three gold fleurs-de-lys. It was flown above fortifications in the early years of the colony. For instance, it was flown above the lodgings of Pierre Du Gua de Monts at Île Sainte-Croix in 1604. There is some evidence that the banner also flew above Samuel de Champlain's habitation in 1608. ... the completely white flag of the French Royal Navy was flown from ships, forts and sometimes at land-claiming ceremonies.

- ^ "INQUINTE.CA | CANADA 150 Years of History ~ The story behind the flag". inquinte.ca.

When Canada was settled as part of France and dubbed "New France," two flags gained national status. One was the Royal Banner of France. This featured a blue background with three gold fleurs-de-lis. A white flag of the French Royal Navy was also flown from ships and forts and sometimes flown at land-claiming ceremonies.

- ^ Wallace, W. Stewart (1948). "Flag of New France". The Encyclopedia of Canada. Vol. II. Toronto: University Associates of Canada. pp. 350–351.

During the French régime in Canada, there does not appear to have been any French national flag in the modern sense of the term. The "Banner of France", which was composed of fleur-de-lys on a blue field, came nearest to being a national flag, since it was carried before the king when he marched to battle, and thus in some sense symbolized the kingdom of France. During the later period of French rule, it would seem that the emblem...was a flag showing the fleur-de-lys on a white ground... as seen in Florida. There were, however, 68 flags authorized for various services by Louis XIV in 1661; and a number of these were doubtless used in New France

- ^ Ekberg, Carl (2000). French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times. Urbana and Chicago, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780252069246. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ Carrière, J.-M. (1939). "Creole Dialect of Missouri". American Speech. 14 (2). Duke University Press: 109–119. doi:10.2307/451217. JSTOR 451217.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).