Back غلوبيولين مناعي أ Arabic İmmunoqlobin A Azerbaijani Immunoglobulina A Catalan Imunoglobulin A Czech Immunoglobulin A Danish Immunglobulin A German Ανοσοσφαιρίνη A Greek Inmunoglobulina A Spanish A immunoglobulina Basque ایمونوگلوبولین ای Persian

Immunoglobulin A (Ig A, also referred to as sIgA in its secretory form) is an antibody that plays a role in the immune function of mucous membranes. The amount of IgA produced in association with mucosal membranes is greater than all other types of antibody combined.[3] In absolute terms, between three and five grams are secreted into the intestinal lumen each day.[4] This represents up to 15% of total immunoglobulins produced throughout the body.[5]

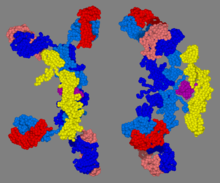

IgA has two subclasses (IgA1 and IgA2) and can be produced as a monomeric as well as a dimeric form. The IgA dimeric form is the most prevalent and, when it has bound the Secretory component, is also called secretory IgA (sIgA). sIgA is the main immunoglobulin found in mucous secretions, including tears, saliva, sweat, colostrum and secretions from the genitourinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, prostate and respiratory epithelium. It is also found in small amounts in blood. The secretory component of sIgA protects the immunoglobulin from being degraded by proteolytic enzymes; thus, sIgA can survive in the harsh gastrointestinal tract environment and provide protection against microbes that multiply in body secretions.[6] sIgA can also inhibit inflammatory effects of other immunoglobulins.[7] IgA is a poor activator of the complement system, and opsonizes only weakly.[8]

- ^ Bonner A, Almogren A, Furtado PB, Kerr MA, Perkins SJ (January 2009). "Location of secretory component on the Fc edge of dimeric IgA1 reveals insight into the role of secretory IgA1 in mucosal immunity". Mucosal Immunology. 2 (1): 74–84. doi:10.1038/mi.2008.68. PMID 19079336.

- ^ Bonner A, Almogren A, Furtado PB, Kerr MA, Perkins SJ (February 2009). "The nonplanar secretory IgA2 and near planar secretory IgA1 solution structures rationalize their different mucosal immune responses". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (8): 5077–87. doi:10.1074/jbc.M807529200. PMC 2643523. PMID 19109255.

- ^ Făgărășan S.; Honjo T. (January 2003). "Intestinal IgA synthesis: regulation of front-line body defences". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 3 (1): 63–72. doi:10.1038/nri982. PMID 12511876. S2CID 2586305.

- ^ Brandtzaeg P, Pabst R (November 2004). "Let's go mucosal: communication on slippery ground". Trends in Immunology. 25 (11): 570–7. doi:10.1016/j.it.2004.09.005. PMID 15489184.

- ^ Macpherson AJ, Slack E (November 2007). "The functional interactions of commensal bacteria with intestinal secretory IgA". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 23 (6): 673–8. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f0d012. PMID 17906446. S2CID 8445606.

- ^ Junqueira LC, Carneiro J (2003). Basic Histology. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-8385-0590-8.[page needed]

- ^ Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C (April 2005). "Mucosal immunity and vaccines". Nature Medicine. 11 (4 Suppl): S45–53. doi:10.1038/nm1213. PMID 15812489.

- ^ Janeway, C.A.; Travers, P.; Walport, M.; Shlomchik, M.J. (2001). Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease (5th ed.). New York: Garland Science. pp. 387–397. ISBN 0-8153-3642-X.