Back Metformien Afrikaans ميتفورمين Arabic مئتفورمین AZB মেটফরমিন Bengali/Bangla Metformina Catalan Metfformin Welsh Metformin Danish Metformin German Μετφορμίνη Greek Metformino Esperanto

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /mɛtˈfɔːrmɪn/, met-FOR-min |

| Trade names | Glucophage, others |

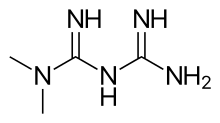

| Other names | N,N-dimethylbiguanide[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a696005 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Antidiabetic agent |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50–60%[11][12] |

| Protein binding | Minimal[11] |

| Metabolism | Not by liver[11] |

| Elimination half-life | 4–8.7 hours[11] |

| Excretion | Urine (90%)[11] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI |

|

| ChEMBL |

|

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.010.472 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C4H11N5 |

| Molar mass | 129.167 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Density | 1.3±0.1[13] g/cm3 |

| |

| |

Metformin, sold under the brand name Glucophage, among others, is the main first-line medication for the treatment of type 2 diabetes,[14][15][16][17] particularly in people who are overweight.[15] It is also used in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome,[16] and is sometimes used as an off-label adjunct to lessen the risk of metabolic syndrome in people who take antipsychotic medication.[18] It has been shown to inhibit inflammation,[19][20] and is not associated with weight gain.[21] Metformin is taken by mouth.[16]

Metformin is generally well tolerated.[22] Common adverse effects include diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain.[16] It has a small risk of causing low blood sugar.[16] High blood lactic acid level (acidosis) is a concern if the medication is used in overly large doses or prescribed in people with severe kidney problems.[23][24]

Metformin is a biguanide anti-hyperglycemic agent.[16] It works by decreasing glucose production in the liver, increasing the insulin sensitivity of body tissues,[16] and increasing GDF15 secretion, which reduces appetite and caloric intake.[25][26][27][28]

Metformin was first described in the scientific literature in 1922 by Emil Werner and James Bell.[29] French physician Jean Sterne began the study in humans in the 1950s.[29] It was introduced as a medication in France in 1957.[16][30] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[31] It is available as a generic medication.[16] In 2022, it was the second most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 86 million prescriptions.[32][33] In Australia, it was one of the top 10 most prescribed medications between 2017 and 2023.[34]

- ^ Sirtori CR, Franceschini G, Galli-Kienle M, Cighetti G, Galli G, Bondioli A, et al. (December 1978). "Disposition of metformin (N,N-dimethylbiguanide) in man". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 24 (6): 683–93. doi:10.1002/cpt1978246683. PMID 710026. S2CID 24531910.

- ^ "Metformin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 10 September 2019. Archived from the original on 16 April 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Metformin Sandoz metformin hydrochloride 850mg tablet bottle (148270)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 27 May 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ "Blooms Metformin XR (Medreich Australia Pty Ltd)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 13 September 2024. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid6847752was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Metformin Hydrochloride". Health Canada. Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ "Glucophage 500 mg film coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 25 October 2022. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Glucophage PIwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ "Metformin and metformin-containing medicines". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 13 October 2016. Archived from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Dunn CJ, Peters DH (May 1995). "Metformin. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus". Drugs. 49 (5): 721–49. doi:10.2165/00003495-199549050-00007. PMID 7601013.

- ^ Hundal RS, Inzucchi SE (2003). "Metformin: new understandings, new uses". Drugs. 63 (18): 1879–94. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363180-00001. PMID 12930161.

- ^ "Metformin". www.chemsrc.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ^ Draznin B, Aroda VR, Bakris G, Benson G, Brown FM, Freeman R, et al. (January 2022). "9. Pharmacologic Approaches to Glycemic Treatment: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022". Diabetes Care. 45 (Suppl 1): S125 – S143. doi:10.2337/dc22-s009. PMID 34964831. S2CID 245538347.

- ^ a b Cosentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, Bailey CJ, Ceriello A, Delgado V, et al. (January 2020). "2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD". European Heart Journal. 41 (2): 255–323. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz486. PMID 31497854.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Metformin Hydrochloride". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 24 December 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ Maruthur NM, Tseng E, Hutfless S, Wilson LM, Suarez-Cuervo C, Berger Z, et al. (June 2016). "Diabetes Medications as Monotherapy or Metformin-Based Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (11): 740–751. doi:10.7326/M15-2650. PMID 27088241. S2CID 32016657.

- ^ de Silva VA, Suraweera C, Ratnatunga SS, Dayabandara M, Wanniarachchi N, Hanwella R (October 2016). "Metformin in prevention and treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Psychiatry. 16 (1): 341. doi:10.1186/s12888-016-1049-5. PMC 5048618. PMID 27716110.

- ^ Lin H, Ao H, Guo G, Liu M (2023). "The Role and Mechanism of Metformin in Inflammatory Diseases". Journal of Inflammation Research. 16: 5545–5564. doi:10.2147/JIR.S436147. PMC 10680465. PMID 38026260.

- ^ Saisho Y (March 2015). "Metformin and Inflammation: Its Potential Beyond Glucose-lowering Effect". Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders Drug Targets. 15 (3): 196–205. doi:10.2174/1871530315666150316124019. PMID 25772174.

- ^ "Type 2 diabetes and metformin. First choice for monotherapy: weak evidence of efficacy but well-known and acceptable adverse effects". Prescrire International. 23 (154): 269–272. November 2014. PMID 25954799.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

pmid26680745was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Blumenberg A, Benabbas R, Sinert R, Jeng A, Wiener SW (April 2020). "Do Patients Die with or from Metformin-Associated Lactic Acidosis (MALA)? Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of pH and Lactate as Predictors of Mortality in MALA". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 16 (2): 222–229. doi:10.1007/s13181-019-00755-6. PMC 7099117. PMID 31907741.

- ^ Lipska KJ, Bailey CJ, Inzucchi SE (June 2011). "Use of metformin in the setting of mild-to-moderate renal insufficiency". Diabetes Care. 34 (6): 1431–7. doi:10.2337/dc10-2361. PMC 3114336. PMID 21617112.

- ^ Coll AP, Chen M, Taskar P, Rimmington D, Patel S, Tadross JA, et al. (February 2020). "GDF15 mediates the effects of metformin on body weight and energy balance". Nature. 578 (7795): 444–448. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1911-y. PMC 7234839. PMID 31875646.

- ^ Day EA, Ford RJ, Smith BK, Mohammadi-Shemirani P, Morrow MR, Gutgesell RM, et al. (December 2019). "Metformin-induced increases in GDF15 are important for suppressing appetite and promoting weight loss". Nature Metabolism. 1 (12): 1202–1208. doi:10.1038/s42255-019-0146-4. PMID 32694673. S2CID 213199603.

- ^ Pappachan JM, Viswanath AK (January 2017). "Medical Management of Diabesity: Do We Have Realistic Targets?". Current Diabetes Reports. 17 (1): 4. doi:10.1007/s11892-017-0828-9. PMID 28101792. S2CID 10289148.

- ^ LaMoia TE, Butrico GM, Kalpage HA, Goedeke L, Hubbard BT, Vatner DF, et al. (March 2022). "Metformin, phenformin, and galegine inhibit complex IV activity and reduce glycerol-derived gluconeogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 119 (10): e2122287119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11922287L. doi:10.1073/pnas.2122287119. PMC 8916010. PMID 35238637.

- ^ a b Fischer J (2010). Analogue-based Drug Discovery II. John Wiley & Sons. p. 49. ISBN 978-3-527-63212-1. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Stargrove MB, Treasure J, McKee DL (2008). Herb, nutrient, and drug interactions: clinical implications and therapeutic strategies. St. Louis, Mo.: Mosby/Elsevier. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-323-02964-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Metformin Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Medicines in the health system". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2 July 2024. Retrieved 30 September 2024.