Back Paleolitikum Afrikaans Altsteinzeit ALS العصر الحجري القديم Arabic Paleolíticu AST Paleolit Azerbaijani Палеолит Bashkir Oidstoazeit BAR Senuojė kūlė gadīnė BAT-SMG Paleolitiko BCL Палеаліт Byelorussian

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

| ↓ Mesolithic |

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (c. 3.3 million – c. 11,700 years ago) (/ˌpeɪlioʊˈlɪθɪk, ˌpæli-/ PAY-lee-oh-LITH-ik, PAL-ee-), also called the Old Stone Age (from Ancient Greek παλαιός (palaiós) 'old' and λίθος (líthos) 'stone'), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehistoric technology.[1] It extends from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominins, c. 3.3 million years ago, to the end of the Pleistocene, c. 11,650 cal BP.[2]

The Paleolithic Age in Europe preceded the Mesolithic Age, although the date of the transition varies geographically by several thousand years. During the Paleolithic Age, hominins grouped together in small societies such as bands and subsisted by gathering plants, fishing, and hunting or scavenging wild animals.[3] The Paleolithic Age is characterized by the use of knapped stone tools,[not verified in body] although at the time humans also used wood and bone tools. Other organic commodities were adapted for use as tools, including leather and vegetable fibers; however, due to rapid decomposition, these have not survived to any great degree.

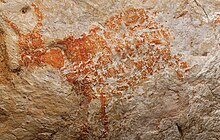

About 50,000 years ago, a marked increase in the diversity of artifacts occurred. In Africa, bone artifacts and the first art appear in the archaeological record. The first evidence of human fishing is also noted, from artifacts in places such as Blombos Cave in South Africa. Archaeologists classify artifacts of the last 50,000 years into many different categories, such as projectile points, engraving tools, sharp knife blades, and drilling and piercing tools.

Humankind gradually evolved from early members of the genus Homo—such as Homo habilis, who used simple stone tools—into anatomically modern humans as well as behaviourally modern humans by the Upper Paleolithic.[4] During the end of the Paleolithic Age, specifically the Middle or Upper Paleolithic Age, humans began to produce the earliest works of art and to engage in religious or spiritual behavior such as burial and ritual.[5][page needed][6][need quotation to verify] Conditions during the Paleolithic Age went through a set of glacial and interglacial periods in which the climate periodically fluctuated between warm and cool temperatures.

By c. 50,000 – c. 40,000 BP, the first humans set foot in Australia. By c. 45,000 BP, humans lived at 61°N latitude in Europe.[7] By c. 30,000 BP, Japan was reached, and by c. 27,000 BP humans were present in Siberia, above the Arctic Circle.[7] By the end of the Upper Paleolithic Age humans had crossed Beringia and expanded throughout the Americas continents.[8][9]

- ^ Christian, David (2014). Big History: Between Nothing and Everything. New York: McGraw Hill Education. p. 93.

- ^ Toth, Nicholas; Schick, Kathy (2007). "21 Overview of Paleolithic Archeology". In Henke, H. C. Winfried; Hardt, Thorolf; Tatersall, Ian (eds.). Handbook of Paleoanthropology. Vol. 3. Berlin; Heidelberg; New York: Springer. pp. 1943–1963. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33761-4_64. ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4.

- ^ McClellan (2006). Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 6–12. ISBN 978-0-8018-8360-6.

- ^ Contributed by Richard B. Potts, B.A., Ph.D. "Human Evolution". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lieberman, Philip (1991). Uniquely Human. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-92183-2.

- ^ Kusimba, Sibel (2003). African Foragers: Environment, Technology, Interactions. Rowman Altamira. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-7591-0154-8.

- ^ a b Weinstock, John. "Sami Prehistory Revisited: transactions, admixture and assimilation in the phylogeographic picture of Scandinavia". University of Texas.

- ^ Goebel, Ted; Waters, Michael R.; O'Rourke, Dennis H. (14 March 2008). "The Late Pleistocene Dispersal of Modern Humans in the Americas" (PDF). Science. 319 (5869): 1497–502. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1497G. doi:10.1126/science.1153569. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 18339930. S2CID 36149744. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ Bennett, Matthew R.; Bustos, David; Pigati, Jeffrey S.; Springer, Kathleen B.; Urban, Thomas M.; Holliday, Vance T.; Reynolds, Sally C.; Budka, Marcin; Honke, Jeffrey S.; Hudson, Adam M.; Fenerty, Brendan; Connelly, Clare; Martinez, Patrick J.; Santucci, Vincent L.; Odess, Daniel (23 September 2021). "Evidence of humans in North America during the Last Glacial Maximum". Science. 373 (6562): 1528–1531. Bibcode:2021Sci...373.1528B. doi:10.1126/science.abg7586. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 34554787. S2CID 237616125.