Back انتواع خارجي Arabic Перипатрично видообразуване Bulgarian Peripatrična specijacija BS Especiació peripàtrica Catalan گونهزایی پیرابوم Persian Spéciation péripatrique French Especiación peripátrica Galician Spesiasi peripatrik ID 근소적 종분화 Korean Peripatrische soortvorming Dutch

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

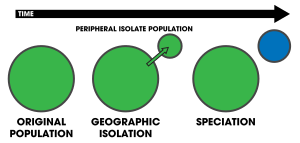

Peripatric speciation is a mode of speciation in which a new species is formed from an isolated peripheral population.[1]: 105 Since peripatric speciation resembles allopatric speciation, in that populations are isolated and prevented from exchanging genes, it can often be difficult to distinguish between them,[2] and peripatric speciation may be considered one type or model of allopatric speciation.[3] The primary distinguishing characteristic of peripatric speciation is that one of the populations is much smaller than the other, as opposed to (other types of) allopatric speciation, in which similarly-sized populations become separated. The terms peripatric and peripatry are often used in biogeography, referring to organisms whose ranges are closely adjacent but do not overlap, being separated where these organisms do not occur—for example on an oceanic island compared to the mainland. Such organisms are usually closely related (e.g. sister species); their distribution being the result of peripatric speciation.

The concept of peripatric speciation was first outlined by the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr in 1954.[4] Since then, other alternative models have been developed such as centrifugal speciation, that posits that a species' population experiences periods of geographic range expansion followed by shrinking periods, leaving behind small isolated populations on the periphery of the main population. Other models have involved the effects of sexual selection on limited population sizes. Other related models of peripherally isolated populations based on chromosomal rearrangements have been developed such as budding speciation and quantum speciation.

The existence of peripatric speciation is supported by observational evidence and laboratory experiments.[1]: 106 Scientists observing the patterns of a species biogeographic distribution and its phylogenetic relationships are able to reconstruct the historical process by which they diverged. Further, oceanic islands are often the subject of peripatric speciation research due to their isolated habitats—with the Hawaiian Islands widely represented in much of the scientific literature.

- ^ a b Jerry A. Coyne; H. Allen Orr (2004), Speciation, Sinauer Associates, pp. 1–545, ISBN 978-0-87893-091-3

- ^ Lucinda P. Lawson, John M Bates, Michele Menegon, & Simon P. Loader (2015), "Divergence at the edges: peripatric isolation in the montane spiny throated reed frog complex", BMC Evolutionary Biology, 15 (128): 128, Bibcode:2015BMCEE..15..128L, doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0384-3, PMC 4487588, PMID 26126573

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Peripatric speciation". Understanding Evolution. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ Ernst Mayr. (1954). Change of genetic environment and evolution. In J. Huxley, A. C. Hardy & E. B. Ford. (eds) Evolution as a Process, Unwin Brothers, London. Pp. 157–180.