Back مرحاض ذو حفرة Arabic খাটা পায়খানা Bengali/Bangla Latrina de fossa Catalan Тул ям CV Do nugododeƒe EE Letrina de hoyo Spanish توالت گودالی Persian Latrine à fosse simple French Shaddar gargajiya Hausa खुड्डी शौचालय Hindi

| Pit latrine | |

|---|---|

| Synonym | Pit toilet, household latrine, long drop |

| |

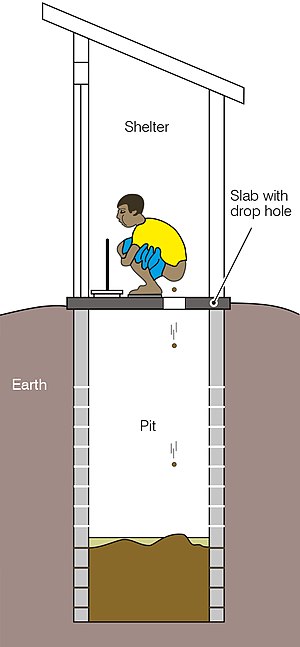

| A simple pit latrine with a squatting pan and shelter[1] | |

| Position in sanitation chain | User interface, collection and storage (on-site) |

| Application level | Household level |

| Management level | Household, public, shared |

| Inputs | Feces, urine[2] |

| Outputs | Fecal sludge[3] |

| Types | With or without water seal, single or twin pit |

| Construction cost | Cheapest form of basic sanitation[4] |

| Maintenance cost | US$2–12/person/year as of 2011 (not including emptying)[5] |

| Environmental concerns | Groundwater pollution[3] |

| Number of users | 1.8 billion people (2013)[6] |

A pit latrine, also known as pit toilet, is a type of toilet that collects human waste in a hole in the ground.[2] Urine and feces enter the pit through a drop hole in the floor, which might be connected to a toilet seat or squatting pan for user comfort.[2] Pit latrines can be built to function without water (dry toilet) or they can have a water seal (pour-flush pit latrine).[7] When properly built and maintained, pit latrines can decrease the spread of disease by reducing the amount of human feces in the environment from open defecation.[4][8] This decreases the transfer of pathogens between feces and food by flies.[4] These pathogens are major causes of infectious diarrhea and intestinal worm infections.[8] Infectious diarrhea resulted in about 700,000 deaths in children under five years old in 2011 and 250 million lost school days.[8][9] Pit latrines are a low-cost method of separating feces from people.[4]

A pit latrine generally consists of three major parts: a hole in the ground, a concrete slab or floor with a small hole, and a shelter.[7] The shelter is also called an outhouse.[10] The pit is typically at least three meters (10 ft) deep and one meter (3 ft) across.[7] The hole in the slab should not be larger than 25 cm (10 in) to prevent children falling in.[4] Light should be prevented from entering the pit to reduce access by flies.[4] This may require the use of a lid to cover the hole in the floor when not in use.[4] The World Health Organization recommends that pits be built a reasonable distance from the house, ideally balancing easy access against smell.[4] The distance from water wells and surface water should be at least 10 m (30 ft) to decrease the risk of groundwater pollution.[11] When the pit fills to within 0.5 m (1+1⁄2 ft) of the top, it should be either emptied or a new pit constructed and the shelter moved or re-built at the new location.[12] Fecal sludge management involves emptying pits as well as transporting, treating and using the collected fecal sludge.[3] If this is not carried out properly, water pollution and public health risks can occur.[3]

A basic pit latrine can be improved in a number of ways.[2] One includes adding a ventilation pipe from the pit to above the structure.[12] This improves airflow and decreases the smell of the toilet.[12] It also can reduce flies when the top of the pipe is covered with mesh (usually made out of fiberglass).[12] In these types of toilets a lid need not be used to cover the hole in the floor.[12] Other possible improvements include a floor constructed so fluid drains into the hole and a reinforcement of the upper part of the pit with bricks, blocks, or cement rings to improve stability.[7][12] In developing countries the cost of a simple pit toilet is typically between US$25 and $60.[13] Recurring expenditure costs are between US$1.5 and $4 per person per year for a traditional pit latrine, and up to three times higher for a pour flush pit latrine (without the costs of emptying).[5]

As of 2013 pit latrines are used by an estimated 1.77 billion people, mostly in developing countries.[6] About 892 million people (12 percent of the global population) practiced open defecation in 2016, mostly because they have no toilets.[14] Southern Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa have the lowest access to toilets.[14] The Indian government has been running a campaign called "Swachh Bharat Abhiyan" (Clean India Mission in English) since 2014 in order to eliminate open defecation by convincing people in rural areas to purchase, construct and use toilets, mainly pit latrines.[15][16] As a result, sanitation coverage in India has increased from just 39% in October 2014 to almost 98% in 2019.[17] It is estimated that 85 million pit latrines have been built due to that campaign as of 2018.[18][19] Another example from India is the "No Toilet, No Bride" campaign which promotes toilet uptake by encouraging women to refuse to marry men who do not own a toilet.[20][21]

- ^ WEDC (15 January 2011). Latrine slabs: an engineer's guide, WEDC Guide 005 (PDF). Water, Engineering and Development Centre The John Pickford Building School of Civil and Building Engineering Loughborough University. p. 22. ISBN 978-1843801436. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Fact sheets on environmental sanitation". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 7 September 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ a b c d Strande, Linda; Brdjanovic, Damir (2014). Faecal Sludge Management: Systems Approach for Implementation and Operation. IWA Publishing. pp. 1, 6, 46. ISBN 978-1780404721.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Simple pit latrine (fact sheet 3.4)". who.int. 1996. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ a b Sanitation and Hygiene in Africa Where Do We Stand?. Intl Water Assn. 2013. p. 161. ISBN 978-1780405414. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017.

- ^ a b Graham, JP; Polizzotto, ML (May 2013). "Pit latrines and their impacts on groundwater quality: a systematic review". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (5): 521–530. Bibcode:2013EnvHP.121..521G. doi:10.1289/ehp.1206028. PMC 3673197. PMID 23518813.

- ^ a b c d Tilley, E.; Ulrich, L.; Lüthi, C.; Reymond, Ph.; Zurbrügg, C. (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies (2 ed.). Dübendorf, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag). ISBN 978-3906484570.

- ^ a b c "Call to action on sanitation" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- ^ Walker, CL; Rudan, I; Liu, L; Nair, H; Theodoratou, E; Bhutta, ZA; O'Brien, KL; Campbell, H; Black, RE (20 April 2013). "Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea". Lancet. 381 (9875): 140514–16. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60222-6. PMC 7159282. PMID 23582727.

- ^ Understanding Viruses. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2016. p. 456. ISBN 978-1284025927.

- ^ Communicable Disease Epidemiology and Control: A Global Perspective. CABI. 2005. p. 52. ISBN 978-0851990743.

- ^ a b c d e f François Brikké (2003). Linking technology choice with operation and maintenance in the context of community water supply and sanitation (PDF). World Health Organization. p. 108. ISBN 9241562153. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 November 2005.

- ^ Selendy, Janine M. H. (2011). Water and sanitation-related diseases and the environment challenges, interventions, and preventive measures. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 25. ISBN 978-1118148600. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Progress on Drinking Water, Sanitation and Hygiene: 2017 Update and SDG Baselines". UNICEF. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), World Health Organization (WHO). 2017. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Sanjai, P (30 July 2018). "World's Biggest Toilet-Building Spree Is Under Way in India". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "Restructuring of the Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan into Swachh Bharat Mission". pib.nic.in. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "A Clean (Sampoorna Swachh) India". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ "3 Years Of Swachh Bharat: 50 Million More Toilets; Unclear How Many Are Used". Fact Checker. 2 October 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ "Swachh Bharat Mission – Gramin, Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation". swachhbharatmission.gov.in. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Global Problems, Smart Solutions: Costs and Benefits. Cambridge University Press. 2013. p. 623. ISBN 978-1107435247.

- ^ Stopnitzky, Yaniv (12 December 2011). "Haryana's scarce women tell potential suitors: "No loo, no I do"". Development Impact. Blog of World Bank. Archived from the original on 1 March 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2014.