Back Kolonisasie van Ulster Afrikaans Colonización del Úlster AST Colonització de l'Ulster Catalan Plantation of Ulster German Colonización del Úlster Spanish Ulsterko kolonizazioa Basque Ulsterin uudisasutus Finnish Plandáil Uladh Irish Օլսթերի գաղութացում Armenian Kolonisasi Ulster ID

The Plantation of Ulster (Irish: Plandáil Uladh; Ulster Scots: Plantin o Ulstèr[1]) was the organised colonisation (plantation) of Ulster – a province of Ireland – by people from Great Britain during the reign of King James VI and I.

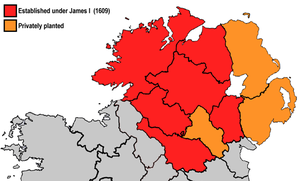

Small privately funded plantations by wealthy landowners began in 1606,[2][3][4] while the official plantation began in 1609. Most of the land had been confiscated from the native Gaelic chiefs, several of whom had fled Ireland for mainland Europe in 1607 following the Nine Years' War against English rule. The official plantation comprised an estimated half a million acres (2,000 km2) of arable land in counties Armagh, Cavan, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Donegal, and Londonderry.[5] Land in counties Antrim, Down, and Monaghan was privately colonised with the king's support.[2][3][4]

Among those involved in planning and overseeing the plantation were King James, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Arthur Chichester, and the Attorney-General for Ireland, John Davies.[6] They saw the plantation as a means of controlling, anglicising,[7] and "civilising" Ulster.[8] The province was almost wholly Gaelic, Catholic, and rural and had been the region most resistant to English control. The plantation was also meant to sever the ties of the Gaelic clans of Ulster with those from the Highlands of Scotland,[9] as it meant a strategic threat to England.[10] The colonists (or "British tenants")[11][12] were required to be English-speaking, Protestant,[6][13] and loyal to the king. Some of the landlords and settlers, however, were Catholic.[14][15][16] The Scottish settlers were mostly Presbyterian Lowlanders and the English settlers were mostly Anglican Northerners, which their culture differed from that of the native Irish.[11] Although some "loyal" natives were granted land, the native Irish reaction to the plantation was generally hostile,[17] and native writers lamented what they saw as the decline of Gaelic society and the influx of foreigners.[18]

The Plantation of Ulster was the biggest of the plantations of Ireland.[19] It led to the founding of many of Ulster's towns and created a lasting Ulster Protestant community in the province with ties to Britain. It also resulted in many of the native Irish nobility losing their land and led to centuries of ethnic and sectarian animosity, which at times spilled into conflict, notably in the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and, more recently, the Troubles.

- ^ "Monea Castle and Derrygonnelly Church: Ulster-Scots translation" (PDF). DoENI.gov.uk. Northern Ireland Environment Agency, Department of the Environment. 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2011.

- ^ a b Stewart (1989), p. 38.

- ^ a b Falls (1996), pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b Perceval-Maxwell (1999), p. 55.

- ^ & Jackson (1973), p. 51.

- ^ a b MacRaild & Smith (2012), p. 142: "Advisors to King James VI/I, notably Arthur Chichester, Lord Deputy from 1604, and Sir John Davies, the lawyer, favoured the plantation as a definitive response to the challenges of ruling Ireland. ... Undertakers, servitors and natives were granted large blocks of land as long as they planted English-speaking Protestants".

- ^ Lenihan (2007), p. 43: "According to the Lord Deputy Chichester, the plantation would 'separate the Irish by themselves ... [so they would], in heart in tongue and every way else become English"

- ^ Bardon (2011), p. 214: "To King James the Plantation of Ulster would be a civilising enterprise which would 'establish the true religion of Christ among men ... almost lost in superstition'. In short, he intended his grandiose scheme would bring the enlightenment of the Reformation to one of the most remote and benighted provinces in his kingdom. Yet some of the most determined planters were, in fact, Catholics."

- ^ Ellis, Steven (2014). The Making of the British Isles: The State of Britain and Ireland, 1450-1660. Routledge. p. 296.

- ^ "2. The Plantations: Sowing the seeds of Ireland's religious geographies". Troubled Geographies: A Spatial History of Religion and Society in Ireland. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ a b Curtis (2000), p. 198.

- ^ Moody & Martin (1984), p. 190.

- ^ "BBC History – The Plantation of Ulster – Religion". Archived from the original on 4 December 2019. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ Bardon (2011), pp. ix–x: "Many will be surprised that three amongst the most energetic planters were Catholics. Sir Randall MacDonell, Earl of Antrim, ... George Tuchet, 18th Baron Audley, ... Sir George Hamilton of Greenlaw, together with his relatives ... made his well-managed estate in the Strabane area a haven for Scottish Catholics".

- ^ Bardon (2011), p. 214: "The result was that over the ensuing decades many Catholic Scots ... were persuaded to settle in this part of Tyrone [Strabane]".

- ^ Blaney, Roger (2012). Presbyterians and the Irish Language. Ulster Historical Foundation. pp. 6–16. ISBN 978-1-908448-55-2.

- ^ "BBC History – The Plantation of Ulster – Reaction of the natives". Archived from the original on 31 December 2019.

- ^ Horning, Audrey (2013). Ireland in the Virginian Sea: Colonialism in the British Atlantic. University of North Carolina Press. p. 179.

- ^ Dorney, John (2 June 2024). "The Plantation of Ulster: A Brief Overview". The Irish Story. Retrieved 30 December 2024.