Back Robert Koch Afrikaans Robert Koch ALS ሮቤርት ኮኽ Amharic Robert Koch AN روبرت كوخ Arabic روبيرت كوخ ARZ Robert Koch AST Robert Koch Aymara Robert Kox Azerbaijani روبرت کوخ AZB

Robert Koch | |

|---|---|

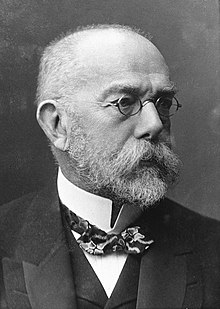

Koch c. 1900 | |

| Born | Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch 11 December 1843 |

| Died | 27 May 1910 (aged 66) |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | University of Göttingen |

| Known for | Koch's postulates Koch–Pasteur rivalry Bacterial culture method Germ theory of disease Medical microbiology Discovery of anthrax bacillus Discovery of tuberculosis bacillus and tuberculin Discovery of cholera bacillus |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Microbiology |

| Institutions | Imperial Health Office, Berlin University of Berlin |

| Doctoral advisor | Georg Meissner |

| Other academic advisors | Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle Karl Ewald Hasse Rudolf Virchow |

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch (/kɒx/ KOKH;[1][2] German: [ˈʁoːbɛʁt ˈkɔx] ⓘ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he is regarded as one of the main founders of modern bacteriology. As such he is popularly nicknamed the father of microbiology (with Louis Pasteur[3]), and as the father of medical bacteriology.[4][5] His discovery of the anthrax bacterium (Bacillus anthracis) in 1876 is considered as the birth of modern bacteriology.[6] Koch used his discoveries to establish that germs "could cause a specific disease"[7] and directly provided proofs for the germ theory of diseases, therefore creating the scientific basis of public health,[8] saving millions of lives.[9] For his life's work Koch is seen as one of the founders of modern medicine.

While working as a private physician, Koch developed many innovative techniques in microbiology. He was the first to use the oil immersion lens, condenser, and microphotography in microscopy. His invention of the bacterial culture method using agar and glass plates (later developed as the Petri dish by his assistant Julius Richard Petri) made him the first to grow bacteria in the laboratory. In appreciation of his work, he was appointed to government advisor at the Imperial Health Office in 1880, promoted to a senior executive position (Geheimer Regierungsrat) in 1882, Director of Hygienic Institute and Chair (Professor of hygiene) of the Faculty of Medicine at Berlin University in 1885, and the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases (later renamed Robert Koch Institute after his death) in 1891.

The methods Koch used in bacteriology led to the establishment of a medical concept known as Koch's postulates, four generalized medical principles to ascertain the relationship of pathogens with specific diseases. The concept is still in use in most situations and influences subsequent epidemiological principles such as the Bradford Hill criteria.[10] A major controversy followed when Koch discovered tuberculin as a medication for tuberculosis which was proven to be ineffective, but developed for diagnosis of tuberculosis after his death. For his research on tuberculosis, he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1905.[11] The day he announced the discovery of the tuberculosis bacterium, 24 March 1882, has been observed by the World Health Organization as "World Tuberculosis Day" every year since 1982.

- ^ "Koch". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ^ "Koch". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

- ^ Fleming, Alexander (1952). "Freelance of Science". British Medical Journal. 2 (4778): 269. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4778.269. PMC 2020971.

- ^ Tan, S. Y.; Berman, E. (2008). "Robert Koch (1843-1910): father of microbiology and Nobel laureate". Singapore Medical Journal. 49 (11): 854–855. PMID 19037548.

- ^ Gradmann, Christoph (2006). "Robert Koch and the white death: from tuberculosis to tuberculin". Microbes and Infection. 8 (1): 294–301. doi:10.1016/j.micinf.2005.06.004. PMID 16126424.

- ^ Lakhani, S. R. (1993). "Early clinical pathologists: Robert Koch (1843-1910)". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 46 (7): 596–598. doi:10.1136/jcp.46.7.596. PMC 501383. PMID 8157741.

- ^ "A Theory of Germs". Science, Medicine, and Animals. National Academies Press (US). 2023-10-20.

- ^ Lakhtakia, Ritu (2014). "The Legacy of Robert Koch: Surmise, search, substantiate". Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 14 (1): e37–41. doi:10.12816/0003334. PMC 3916274. PMID 24516751.

- ^ "1843: Robert Koch: The Man who Saved Millions of Lives | History.info". 2019-12-10.

- ^ Margo, Curtis E. (2011-04-11). "From Robert Koch to Bradford Hill: Chronic Infection and the Origins of Ocular Adnexal Cancers". Archives of Ophthalmology. 129 (4): 498–500. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.53. ISSN 0003-9950. PMID 21482875.

- ^ Brock, Thomas. Robert Koch: A life in medicine and bacteriology. ASM Press: Washington DC, 1999. Print.