| Second Taranaki War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of New Zealand Wars | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Taranaki Māori | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 | 1,500 (including women and children) | ||||||

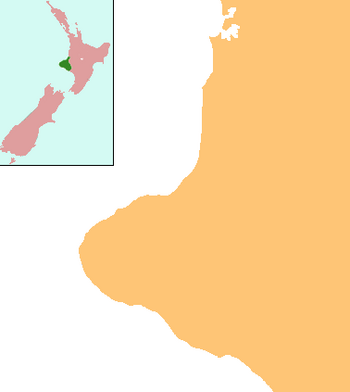

The Second Taranaki War is a term used by some historians for the period of hostilities between Māori and the New Zealand Government in the Taranaki district of New Zealand between 1863 and 1866. The term is avoided by some historians, who either describe the conflicts as merely a series of West Coast campaigns that took place between the Taranaki War (1860–1861) and Titokowaru's War (1868–69), or an extension of the First Taranaki War.[1]

The conflict, which overlapped the wars in Waikato and Tauranga, was fuelled by a combination of factors: lingering Māori resentment over the sale of land at Waitara in 1860 and government delays in resolving the issue; a large-scale land confiscation policy launched by the government in late 1863; and the rise of the so-called Hauhau movement, an extremist part of the Pai Marire syncretic religion, which was strongly opposed to the alienation of Māori land and eager to strengthen Māori identity.[2] The Hauhau movement became a unifying factor for Taranaki Māori in the absence of individual Māori commanders.

The style of warfare after 1863 differed markedly from that of the 1860-61 conflict, in which Māori had taken set positions and challenged the army to an open contest. From 1863 the army, working with greater numbers of troops and heavy artillery, systematically took possession of Māori land by driving off the inhabitants, adopting a "scorched earth" strategy of laying waste to Māori villages and cultivations, with attacks on villages, whether warlike or otherwise. As the troops advanced, the Government built an expanding line of redoubts, behind which settlers built homes and developed farms. The effect was a creeping confiscation of almost a million acres (4,000 km2) of land, with little distinction between the land of loyal or rebel Māori owners.[3]

The Government's war policy was opposed by the British commander, General Duncan Cameron, who clashed with Governor Sir George Grey and offered his resignation in February 1865. He left New Zealand six months later. Cameron, who viewed the war as a form of land plunder, had urged the Colonial Office to withdraw British troops from New Zealand and from the end of 1865 the Imperial forces began to leave, replaced by an expanding New Zealand military force.[4] Among the new colonial forces were specialist Forest Ranger units, which embarked on lengthy search-and-destroy missions deep into the bush.[5][6]

The Waitangi Tribunal has argued that apart from the attack on Sentry Hill in April 1864, there was an absence of Māori aggression throughout the entire Second War, and that therefore Māori were never actually at war. It concluded: "In so far as Māori fought at all – and few did – they were merely defending their kainga, crops and land against military advance and occupation."[7]

- ^ Belich dismisses as "inappropriate" the description of later conflict as a second Taranaki war. Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict (1st ed.). Auckland: Penguin. p. 120.

- ^ Belich, James (1986). The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict (1st ed.). Auckland: Penguin. pp. 204–205. ISBN 014011162X.

- ^ The Taranaki Report: Kaupapa Tuatahi by the Waitangi Tribunal (PDF), 1996, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007

- ^ Cowan, James (1922). "5: Cameron's West Coast Campaign". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 2.

- ^ Cowan says the first company of New Zealand Forest Rangers was formed soon after a newspaper advertisement was placed in Auckland's Southern Cross newspaper on 31 July 1863. The advertisement said the rangers would emulate the work of the Taranaki Volunteers, formed earlier that year, in "striking terror into the mauauding natives". The 60-strong company was headed by Lieut. William Jackson of Papakura. A second company was formed later in 1863 under Captain Gustavus Von Tempsky. Cowan, James (1922). "29. The Forest Rangers". The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Maori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period. Vol. 1.

- ^ "Notice. To All Militiamen and Others". The Daily Southern Cross. Vol. 19, no. 1884. 31 July 1863. p. 1.

- ^ "4", The Taranaki Report - Kaupapa Tuatahi, Waitangi Tribunal, 1996