Back Разпространение на будизма по пътя на коприната Bulgarian রেশম পথে বৌদ্ধধর্মের প্রসারণ Bengali/Bangla Transmissió del budisme per la Ruta de la Seda Catalan Transmisión del budismo por la Ruta de la Seda Spanish Expansion du bouddhisme via la route de la soie French रेशम मार्ग से बौद्ध धर्म का प्रसार Hindi A buddhizmus terjedése a selyemúton Hungarian Penyebaran Buddhisme di sepanjang Jalur Sutra ID 仏教のシルクロード伝播 Japanese रेशीम मार्गाद्वारे बौद्ध धर्माचा प्रसार Marathi

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with Sinocentric and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. The specific issue is: The article is not only written from the perspective of Chinese Buddhism but also pays too overtly portrays the involvement of Central Asia. (June 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism |

|---|

|

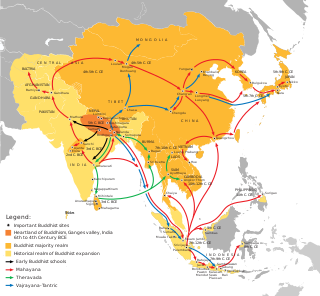

Mahāyāna Buddhism entered Han China via the Silk Road, beginning in the 1st or 2nd century CE.[5][6] The first documented translation efforts by Buddhist monks in China were in the 2nd century CE via the Kushan Empire into the Chinese territory bordering the Tarim Basin under Kanishka.[7][8] These contacts transmitted strands of Sarvastivadan and Tamrashatiya Buddhism throughout the Eastern world.[9]

Theravada Buddhism developed from the Pāli Canon in Sri Lanka Tamrashatiya school and spread throughout Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, Sarvastivada Buddhism was transmitted from North India through Central Asia to China.[9] Direct contact between Central Asian and Chinese Buddhism continued throughout the 3rd to 7th centuries, much into the Tang period. From the 4th century onward, Chinese pilgrims like Faxian (395–414) and later Xuanzang (629–644) started to travel to northern India in order to get improved access to original scriptures. Between the 3rd and 7th centuries, parts of the land route connecting northern India with China was ruled by the Xiongnu, Han dynasty, Kushan Empire, the Hephthalite Empire, the Göktürks, and the Tang dynasty. The Indian form of Buddhist tantra (Vajrayana) reached China in the 7th century. Tibetan Buddhism was likewise established as a branch of Vajrayana, in the 8th century.[10]

But from about this time, the Silk road trade of Buddhism began to decline with the Muslim conquest of Transoxiana (e.g. Battle of Talas), resulting in the Uyghur Khaganate by the 740s.[10] Indian Buddhism declined due to the resurgence of Hinduism and the Muslim conquest of India. Tang-era Chinese Buddhism was briefly repressed in the 9th century (but made a comeback in later dynasties). The Western Liao was a Buddhist Sinitic dynasty based in Central Asia, before Mongol invasion of Central Asia. The Mongol Empire resulted in the further Islamization of Central Asia. They embraced Tibetan Buddhism starting with the Yuan dynasty (Buddhism in Mongolia). The other khanates, the Ilkhanate, Chagatai Khanate, and Golden Horde eventually converted to Islam (Religion in the Mongol Empire#Islam).

Chinese, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, Taiwanese and Southeast Asian traditions of Buddhism continued. As of 2019, China by far had the largest population of Buddhists in the world at nearly 250 million; Thailand comes second at around 70 million (see Buddhism by country).

- ^ Acri, Andrea (20 December 2018). "Maritime Buddhism". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199340378.013.638. ISBN 9780199340378. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, Tafel 19. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- ^ Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin," in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp 134–163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- ^ Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- ^ Zürcher (1972), pp. 22–27.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 30, for the Chinese text from the Hou Hanshu, and p. 31 for a translation of it.

- ^ Zürcher (1972), p. 23.

- ^ Samad, Rafi-us, The Grandeur of Gandhara. The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys, p. 234

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Oscar R. Gómez (2015). Antonio de Montserrat – Biography of the first Jesuit initiated in Tibetan Tantric Buddhism. Editorial MenteClara. p. 32. ISBN 978-987-24510-4-2.