Back Ulysses S. Grant ACE Ulysses S. Grant Afrikaans ዩሊሲስ ግራንት Amharic Ulysses S. Grant AN Ulysses S. Grant ANG يوليسيس جرانت Arabic يوليسيس جرانت ARZ Ulysses S. Grant AST Uliss Qrant Azerbaijani یولیسیز سایمن قرانت AZB

Ulysses S. Grant | |

|---|---|

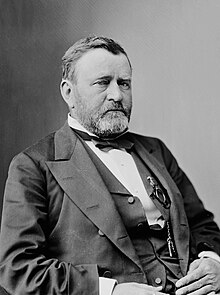

Grant c. 1870–1880 | |

| 18th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Vice President |

|

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Commanding General of the U.S. Army | |

| In office March 9, 1864 – March 4, 1869 | |

| President |

|

| Preceded by | Henry Halleck |

| Succeeded by | William Tecumseh Sherman |

| Acting United States Secretary of War | |

| In office August 12, 1867 – January 14, 1868 | |

| President | Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | Edwin Stanton |

| Succeeded by | Edwin Stanton |

| President of the National Rifle Association | |

| In office 1883–1884[1] | |

| Preceded by | E. L. Molineux |

| Succeeded by | Philip Sheridan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiram Ulysses Grant April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Wilton, New York, U.S. |

| Resting place | Grant's Tomb, New York City |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Education | United States Military Academy |

| Occupation |

|

| Signature | |

| Nicknames |

|

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant;[a] April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as commanding general, Grant led the Union Army to victory in the American Civil War.

Grant was born in Ohio and graduated from the United States Military Academy (West Point) in 1843. He served with distinction in the Mexican–American War, but resigned from the army in 1854 and returned to civilian life impoverished. In 1861, shortly after the Civil War began, Grant joined the Union Army and rose to prominence after securing victories in the western theater. In 1863, he led the Vicksburg campaign that gave Union forces control of the Mississippi River and dealt a major strategic blow to the Confederacy. President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to lieutenant general and command of all Union armies after his victory at Chattanooga. For thirteen months, Grant fought Robert E. Lee during the high-casualty Overland Campaign which ended with the capture of Lee's army at Appomattox, where he formally surrendered to Grant. In 1866, President Andrew Johnson promoted Grant to General of the Army. Later, Grant broke with Johnson over Reconstruction policies. A war hero, drawn in by his sense of duty, Grant was unanimously nominated by the Republican Party and then elected president in 1868.

As president, Grant stabilized the post-war national economy, supported congressional Reconstruction and the Fifteenth Amendment, and prosecuted the Ku Klux Klan. Under Grant, the Union was completely restored. An effective civil rights executive, Grant signed a bill to create the United States Department of Justice and worked with Radical Republicans to protect African Americans during Reconstruction. In 1871, he created the first Civil Service Commission, advancing the civil service more than any prior president. Grant was re-elected in the 1872 presidential election, but was inundated by executive scandals during his second term. His response to the Panic of 1873 was ineffective in halting the Long Depression, which contributed to the Democrats winning the House majority in 1874. Grant's Native American policy was to assimilate Indians into Anglo-American culture. In Grant's foreign policy, the Alabama Claims against Britain were peacefully resolved, but the Senate rejected Grant's annexation of Santo Domingo. In the disputed 1876 presidential election, Grant facilitated the approval by Congress of a peaceful compromise.

Leaving office in 1877, Grant undertook a world tour, becoming the first president to circumnavigate the world. In 1880, he was unsuccessful in obtaining the Republican nomination for a third term. In 1885, impoverished and dying of throat cancer, Grant wrote his memoirs, covering his life through the Civil War, which were posthumously published and became a major critical and financial success. At his death, Grant was the most popular American and was memorialized as a symbol of national unity. Due to the pseudohistorical and negationist mythology of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy spread by Confederate sympathizers around the turn of the 20th century, historical assessments and rankings of Grant's presidency suffered considerably before they began recovering in the 21st century. Grant's critics take a negative view of his economic mismanagement and the corruption within his administration, while his admirers emphasize his policy towards Native Americans, vigorous enforcement of civil and voting rights for African Americans, and securing North and South as a single nation within the Union.[2] Modern scholarship has better appreciated Grant's appointments of Cabinet reformers.

- ^ Utter 2015, p. 141.

- ^ Brands 2012a, p. 636.

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the help page).